Understanding the useEffect Dependency Array

Last week I released an article around Context vs. State vs. Redux. The goal was to try and give developers some pros and cons around each choice and hopefully help you make a better choice about the tool you plan to use. After I released it, I had a couple of people ask me questions around migrations to hooks with regards to using Redux. Some developers were getting issues with useEffect running on every render when using mapDispatchToProps with the connect react-redux HOC.

These were great questions, and after thinking about it for a bit, let's break down why you might be seeing this, and hopefully help you understand why this is happening. So the steps we are going to go through for this article first to explain the background, then solve this issue is

- What is a

useEffecthook? - What is a dependency array?

- Do functions work in a dependency array?

- Can we use

mapStateToDispatchwithuseEffect?

But what about useDispatch?

Before we jump in, I should answer right away; there is a useDispatch hook made available by react-redux. This hook allows us to dispatch as we would with the previous connect HOC, and I highly recommend it going into the future. We'll get into some details how it works with useEffect later in this article, but this is instead focusing on concerns surrounding working on a more "legacy" (if we can call it that) system, that is still using connect.

What is a useEffect

useEffect(() => someCode());

In the simplest terms, useEffect is a hook that allows you to perform side effects in functional components. For even more detail, these effects are only executed after the component has rendered, therefore not blocking the render itself. Often this will be something like a fetch request for some data that the component requires. If we didn't handle side effects, how would a react component render? Can our side-effects block the UI?

Blocking UI

One of the first issues you can come across with effects directly in your code is that you can very easily block the UI from rendering. You won't be able to block it with a request. React will stop you from getting that option. For example, perhaps, at first glance, you decide you'd rather wait until that data is returned before you render anything. React will error if you attempt to use async functions.

Note: Interruptible components are coming up in React! This is going to be through concurrent mode, and I highly recommend reading more about it. Perhaps one of my upcoming articles can explore the code!

I got curious if there was any way I could make React wait for my request, and I couldn't. I even went for a disgusting sleep method, and javascript will correctly finish the function before it jumps back to resolve a promise. I just thought that was kind of neat.

export function CatFacts() {

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/random`;

let data;

function getData() {

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((facts) => (data = facts));

}

getData();

sleep(10000);

return <div>hi{data}</div>;

}

But the above example does illustrate blocking UI. Notice that when a single component is blocked, it will stop the page from rendering as it waits for it to complete. Freezing the UI like this is why we don't want to block any sort of rendering from our side effects, and should be reason enough to try and find some way to isolate that function to after the initial render. Even with that, let's look at examples outside of blocking

Let's assume we don't block the UI, and we still use promises. Our code might look something like:

export function CatFacts() {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/random`;

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((facts) => {

setData(facts.text);

});

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

There's a couple of issues here, lets walk through them one at a time.

Infinite Rerendering

The obvious issue with the code above is that this will create an endless loop of rerendering. This can also happen in useEffect, but there are more rules to make sure this sort of thing doesn't happen. What if we instead try to watch when there is data in the state, something like this:

export function CatFacts() {

const [data, setData] = useState(null);

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/random`;

if (!data) {

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((facts) => {

setData(facts.text);

});

}

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

If we do something like this, it looks a lot better. I mean, the page exists, which is always a step up. The issues with this approach become more apparent as we attempt to reason about this component. Then, from there, as it expands in complexity. So let's ask ourselves, what is data here? For the function itself, it is never the "now." It is always the data of the previous render.

Component Reasoning

In the example above, component reasoning isn't a huge problem. We only want this data once, and we don't worry about loading, etc. But what if the user could pass in the URL, that means that this needs actually to be called when it has data, but only data from the specified URL. This data is from the previous render, not this render.

export function CatFacts({ id }) {

const [data, setData] = useState();

const [urlOfData, setUrlOfData] = useState();

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/${id}`;

if (!data || urlOfData !== id) {

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((facts) => {

setData(facts.text);

setUrlOfData(id);

});

}

return <div>{data}</div>;

}

Now, of course, the useEffect effect is executed after the render, so you could argue it's not that different logistically from what we had previously. But I would argue that by putting something in the useEffect, you are specifically telling the next developer that see's this code, it is not logically in the flow of this component. It is not intended to be read top-down. This function can be thought of as after the rest of this component has executed. Whereas, when something is inline to a functional component, it is assumed that data will be available to the component now.

Now, what if it took a moment to collect the data we wanted? Long running code execution could block the UI from rendering, but for simplicity, I'm just going to use a timeout to fake this.

export function CatFacts({ id }) {

const [data, setData] = useState();

const [urlOfData, setUrlOfData] = useState();

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/${id}`;

if (!data || urlOfData !== id) {

setTimeout(() => {

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((facts) => {

setData(facts.text);

setUrlOfData(id);

});

}, 5000);

}

return <div>Cat Fact: {data}</div>;

}

If you render this, you may notice that the component updates a few times, and requeries it's facts an unpredictable number of times. That's because there are some edge cases in our rendering we now need to keep in mind. If someone updates this while there isn't data, but we were already collecting data to fetch, what happens? What happens if the fetch is requested, but our component updates and requests another?

Imagine we also had interactions that could update the element during this time, which doesn't seem far fetched. It's getting harder and harder to reason exactly the state of our component, and what is happening at a given time. That's not to say that these sorts of things are impossible. But there's got to be a better way, which brings us to one final point.

Functional Purity

If you've worked in the world of "functional" programming, these sorts of effects in your functions are frowned upon. You want to ensure that the component has referential transparency. Side effects take away from the purity of your function. I think functional programming is a great asset to have in your belt, but I don't want to step too far into it today. The easiest way to look at this, is to ask yourself, given that you pass a specific set of inputs to your component, can you expect the same output?

Each side effect we have in our code decreases the likelihood that this is true. Now, before you try to remove absolutely ever ounce of side effects from your system, just keep in mind that user input itself is a side effect, and using a useEffect is still a side effect. Instead, our goal should be to manage, isolate, and control. Handling input like this is also handy in the future for testing, if we want to isolate testing internally to a component or system.

To keep this function more pure, we will be using dependency arrays. We'll take an indepth look at dependency arrays later, but lets take a look at how it looks now. The beauty of using the useEffect hook is also pairing it with the eslint rules that the React team has put out, which will let you know the dependencies that are suggested in the array, and help keep this function as pure as possible.

What does the example looks like as a useEffect?

export function CatFacts({ id }) {

const [data, setData] = useState();

useEffect(() => {

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/${id}`;

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(facts => {

setData(facts.text);

});

}, [id, setData]);

return <div>Cat Fact: {data}</div>;

Note: In the above example, fetch should also be part of the dependency array of the useEffect. I didn't want to add to much noise while we are working through the example, but we will circle back to why it needs to be there later in the article.

Looking at the useEffect, it doesn't look a whole ton different from our previous examples. You'll notice if you add the timeout back to the code example, it will work correctly now as well. We'll break down why that is later on, but notice that we've only really added two new pieces, the useEffect call, and the [id, setData] dependency array.

As I mentioned earlier, I find as I get more familiar with hooks, seeing a useEffect tells me this piece of code won't affect the component until after the initial render. It allows me to quickly find the "side effects" in our code, reducing the cognitive load of running through the component and increasing the readability.

If this is a request we see quite frequently in other components, we could even break it into its own custom hook, which can help even more so with readability:

export function CatFacts({ id }) {

const data = useFetchCatFact(id);

return <div>Cat Fact: {data}</div>;

}

So I should use the useEffect hook on side effects?

Whew, yes. You should. That was a long list of reasons you shouldn't place it inline with the component, but I hope those examples help you understand why this was built. useEffect allows you to:

- not block the UI

- creates a visual "block" of code that is a visible effect.

- keeps your functions pure (or tries to)

- increases the readability of your code

- is easy to extract when needed to custom hooks, so that we can share amongst other components

How does it tie to a class component?

For long time developers of React, the first question that often comes up when I start discussing hooks is what the lifecycle method hooks are? Or when showing them useEffect, I'll be asked: "is this where my componentDidMount happens"? And I'm pretty cautious of answering these questions.

Essentially, what people want is a way to logically map a class component to a functional component 1:1, but I'm hesitant to tie it together that way. You're going to have to break away from thinking in a 1:1 mapping between functional components and class components. Try to reimagine a functional component in a new way, with the most crucial key being that this function can be, and should be, callable at any time. Something isn't only called "on mount". Instead, these should be called with a dependency array, such as a parent's state. And only if that dependency changes, should this be called again.

Dependency arrays works outside of useEffect as well, useCallback and useMemo are other great examples. We want to memoize a function or returned value and only recall/reinitialize those things if specific data changes within the dependency array. But, this should be callable at any time. If you would like to see a more in-depth description of this, I highly recommend checking out Dan Abramovs break down for useEffect.

What is the dependency array?

So I've thrown out the "dependency array" on several occasions, it's best that we break it down and understand what it does. The dependency array is the second optional argument in the useEffect function. As the name implies, it is an array of dependency's that, when changed from the previous render, will recall the effect function defined in the first argument. Lets first look at an example:

function ExampleComponent({ id }) {

useEffect(() => doSomething(id));

return <div></div>;

}

So what is this effect doing exact? Well, every single time this component is updated, it's going to call this useEffect. Perhaps that's something we want, which is acceptable. But more often than not, you likely only want this effect to happen because of something else. Perhaps only when data changes, or maybe when the user first see's the component. In the example above, it seems likely we only want this effect to run when the value in id changes. To do that, we tell the effect "only run when id changes" by placing id in the dependency array.

function ExampleComponent({ id }) {

useEffect(() => doSomething(id), [id]);

return <div></div>;

}

Now, this effect is only executed when id is different than the previous update. I mentioned above that maybe you only want it to run when the user "first sees the component", but I also mention earlier not to think of it as componentDidMount, aren't I contradicting myself. Not quite, because when we are talking about "first sees", we're actually talking about it from a users perspective. Their experience doesn't necessarily need to line up to the code like we always expect. Likely, if we are loading data for a page, the intention is to get that data when the user lands on that page. So, if you wanted to do that, you could do something like this:

function ExampleComponent({ url }) {

useEffect(() => fetchData(url), []);

return <div></div>;

}

This would fetch data only the very first time it's called. And that makes sense right? We've given the effect a dependency array. So our effect thinks "hey, only recall this effect when the values in this array are changed". But there are no values, so it can never update.

But I caution you from building your effects using this style. And the react team does as well. It can lead to confusing, hard to find bugs. Instead, let's think about this component for a moment. We are passing in a URL that defines where we are doing this fetch. What happens if we put the URL in the array like this:

function ExampleComponent({ url }) {

useEffect(() => fetchData(url), [url]);

return <div></div>;

}

There's one of three outcomes.

- That URL never changes, and the effect should only run once.

- That URL is changing but you only wanted it to query the first time.

- That URL is changing, and you want it to query every time it does.

For numbers 1 and 3, the second solution works for you, no matter which way you want to go.

For number 1, if the URL never changes going into the prop after the first time, then it's already working correctly. The URL is the dependency, and that dependency is not intended to change. If for some reason, it does change, you are going to see that error much faster this way, whereas passing an empty array to the dependency array is going to "hide" this bug from you.

For number 3, this is what the dependency array is built for. Each time that URL changes, the effect will be rerun, and you don't need to set up any complex logic to keep it tied to the component like we had to do at the start of the article.

So the only real issue is number 2. But when you stop and think about it, there seems to be a more significant issue to the way you are constructing your components in this example. You want data to come in, but that data is only representational of one instance of your component. If someone were to take a snapshot of your component later on, and pass those inputs to a new component, you would not get the same output.

Our example does not have the referential transparency we want from our components. We should expect that given a set of input, we always receive the same output. And our goal should be that these components should be callable at any time. So I highly encourage that if you are hitting the number 2 outcome, you should rethink your component through.

Do functions work in the dependency array?

Yes! They work the same way as values work in the dependency array, but are instead tied to the reference of that function. Every time the reference of that function changes, we are expected to rerun that effect. In our example above, we cheated because we never actually defined what fetchData was. Let's look at a case where it's a function without our component.

function ExampleComponent({ url }) {

const fetchData = (url) => {

// fetch call here

};

useEffect(() => fetchData(url), [url, fetchData]);

return <div></div>;

}

So that works, right? Well yes, but likely not in the way we want it to, since this is going to again call our effect on every update to the component now. Every time the ExampleComponent is updated, we are going to reinitialize the fetchData function.

Note: Again, we don't want to tie our mental model this into class components, and a lot of people got used to instance variables/methods in class components. In the case of functional components, we don't have "previous values" that exist throughout updates. If a function is called again, all of those values are created again, including the functions.

Your first thought to the problem above may be "well why even have the function in the dependency array if I remove it it it works fine." Yes, in this case, it will work as you expected, but if you are using Reacts ESLint for hooks (and I highly recommend you do), you'll notice it doesn't like that. And that's because of the same reason we talked about above with the on first render and our url prop. This may give us the desired result, but it's could also hide an undesirable bug.

In the example above, we only really expect a single function ever to be used, but you may pass a function as a prop to your component. And that function can be one of several different possible functions. Just like the url prop, we want to make sure that if we receive a new function, that we call out effect once more.

So with the reasoning out of the way, how can we solve our eslint issue, and keep our effect as pure as possible. Well, there's one of three approaches, and each resolves a different usecase.

Approach #1: Move the function into the effect

Usecase: This fetchData call is only ever used in this local useEffect.

If you plan on ever only using this function in this single useEffect, the most straightforward and suggested solution is to move the function directly into the effect closure. This works for everything we discussed previous, and it ensures that our effect function itself is as pure and referentially transparent as possible. It encapsulates the logic to one area and also lets developers know this function is intended as a side effect. So what does that look like

function ExampleComponent({ url }) {

useEffect(() => {

const fetchData = (url) => {

// fetch call here

};

fetchData(url);

}, [url]);

return <div></div>;

}

Since the fetchData function is now part of our effect, it is no longer a dependency of our effect, and we can simply remove it from the dependency array.

Approach #2: Memoize the function with useCallback

Usecase: This function is used in multiple local hooks or is going to be passed down in a child component

useCallback is one of the new hooks available to React. It allows us to memoize a function so that on subsequent updates of the component, the function keeps its referential equality, and therefore does not trigger the effect. useCallbacks use the same dependency array that a useEffect does, so if the values or functions it depends on change, it will be reinitialized. To understand how this works, I think it would be useful to jump into Referential and Value Equality.

Referential Equality vs. Value Equality

For our purposes, there are two types of equality we are looking at, value and referential (also known as a compoud values). Value equality is a bit easier to understand. Value equality is a comparison of the actual "value" of a variable, for example:

function ValueEq() {

const A = "hello";

const B = "goodbye";

const C = "hello";

}

// A === 'hello'

// B === 'goodbye'

// C === 'hello'

In the example above, A === C, while B does not equal either. But if we change A now, the A and C values will not be equal anymore.

function ValueEq() {

let A = "hello";

const B = "goodbye";

const C = "hello";

A = "hi";

}

// A === 'hi'

// B === 'goodbye'

// C === 'hello'

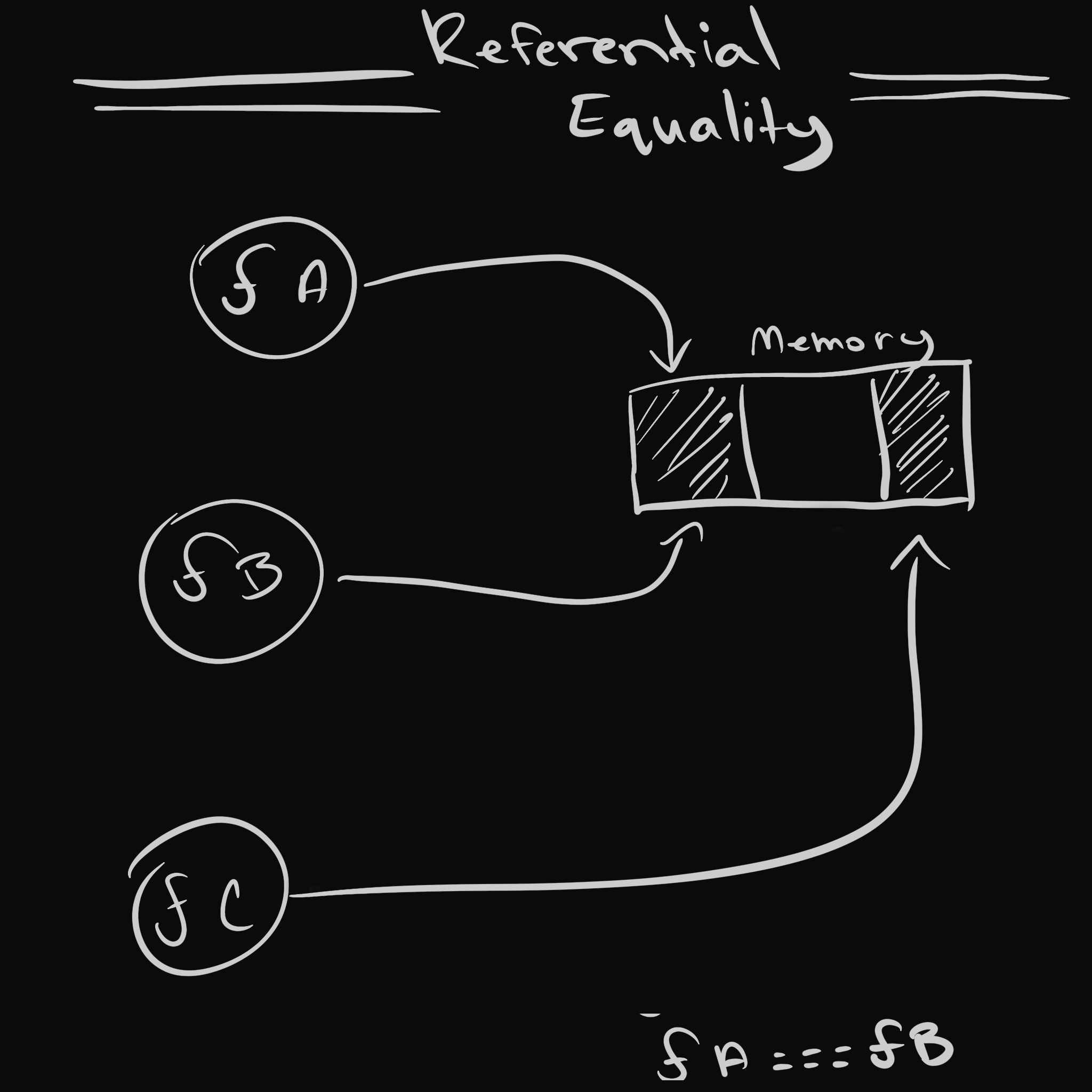

Now, not only are these values no longer equal, but they are pointing to two different spots in memory. We know this because when we change A, C doesn't change with it. If they shared the same spot in memory, both values would update at the same time. That's why these are equality by value, but not referentially equal. Let's see a diagram of what this looks like with our memory:

For primitive values, like a string or integer, we can only compare by value, we don't have a way to store another variables reference. Even if we do something like this:

function eq() {

let A = "hi";

let B = A;

let A = "bye";

}

// A === 'bye'

// B === 'hi'

Despite us pointing the variable B at our A variable, we don't get the spot in memory, we still just get a copy of the value of the variable. Many other languages do have the ability to store the "reference" of a variable, often called a pointer. This is probably most known in the C/C++ languages.

On the other hand, we can compare referential values with compound values, like objects, functions, and arrays.

Note: Technically functions and arrays are also objects in Javascript.

To bring this back around to using functions in the useEffect dependency array, let's take a look at the referential equality of a function:

function RefEq() {

const A = () => {

return 1;

};

const B = A;

const C = () => {

return 1;

};

}

// A === B

// C !== A

Both function A and B are pointing to the same spot in memory. Now, if someone were to reassign A, it would move A to a new place in memory, just like above, and B would still point to the original spot. On the other hand, if A held an object, and we mutated that object, B would also get those updates. Let's take a look at our above code example in a diagram.

Back to our memoized function

So, knowing that we can store the reference to a spot in memory for a given function, we can pass that reference into a dependency array of a useEffect. If the component is rerendered, and that function is not pointing to the same spot in memory (even if it's the same function and parameters), the useEffect will be called again because it sees it as a new function. If we can memoize (remember) the function reference, that means we can stop the useEffect from rerunning unless it truly has changed. Let's see what that looks like.

function ExampleComponent({ url }) {

const fetchData = useCallback(() => {

// fetch call here

}, [url]);

useEffect(() => fetchData(), [fetchData]);

return <div></div>;

}

If you are only going to do a single use of the function, I recommend moving the logic in like above, but this pattern is handy when you need to pass the function into multiple useEffects. You'll find useCallback even handier when passing functions down into child components. If we don't use this pattern, the child component will rerender every update, even if it is memoized. That's because the function will never have the same referential equality to the previous render. Even more, if that child component has any hooks dependent on that function, the will be recalled every time. For that reason, it's always a good bet to build your functions that are being passed to child components with useCallback.

Note: This does not mean you should build every function with useCallback. It's only crucial if it is being passed to child components. Memoizing local functions calls can often add unnecessary overhead and complexity to your code.

So, we know that if we are using our functions in a dependency array, we should memoize them by wrapping this in a useEffect. If we don't do this, the effect will rerun after every update of the component. So then, why in the original example of the useEffect did I now do that with the setData function?

export function CatFacts({ id }) {

const [data, setData] = useState();

useEffect(() => {

const proxyUrl = "https://cors-anywhere.herokuapp.com/";

const targetUrl = `https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/${id}`;

fetch(proxyUrl + targetUrl)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(facts => {

setData(facts.text);

});

}, [id, setData]);

return <div>Cat Fact: {data}</div>;

That's because the function returned in the useState hook is already memoized for you. The same goes for useReducer. And this sets up a fundamental design principle for you as a developer moving forward as you create your hooks. If you are returning a function from your hook, it's highly likely you want that function memoized, so that developers can use them without the extra overhead of handling them.

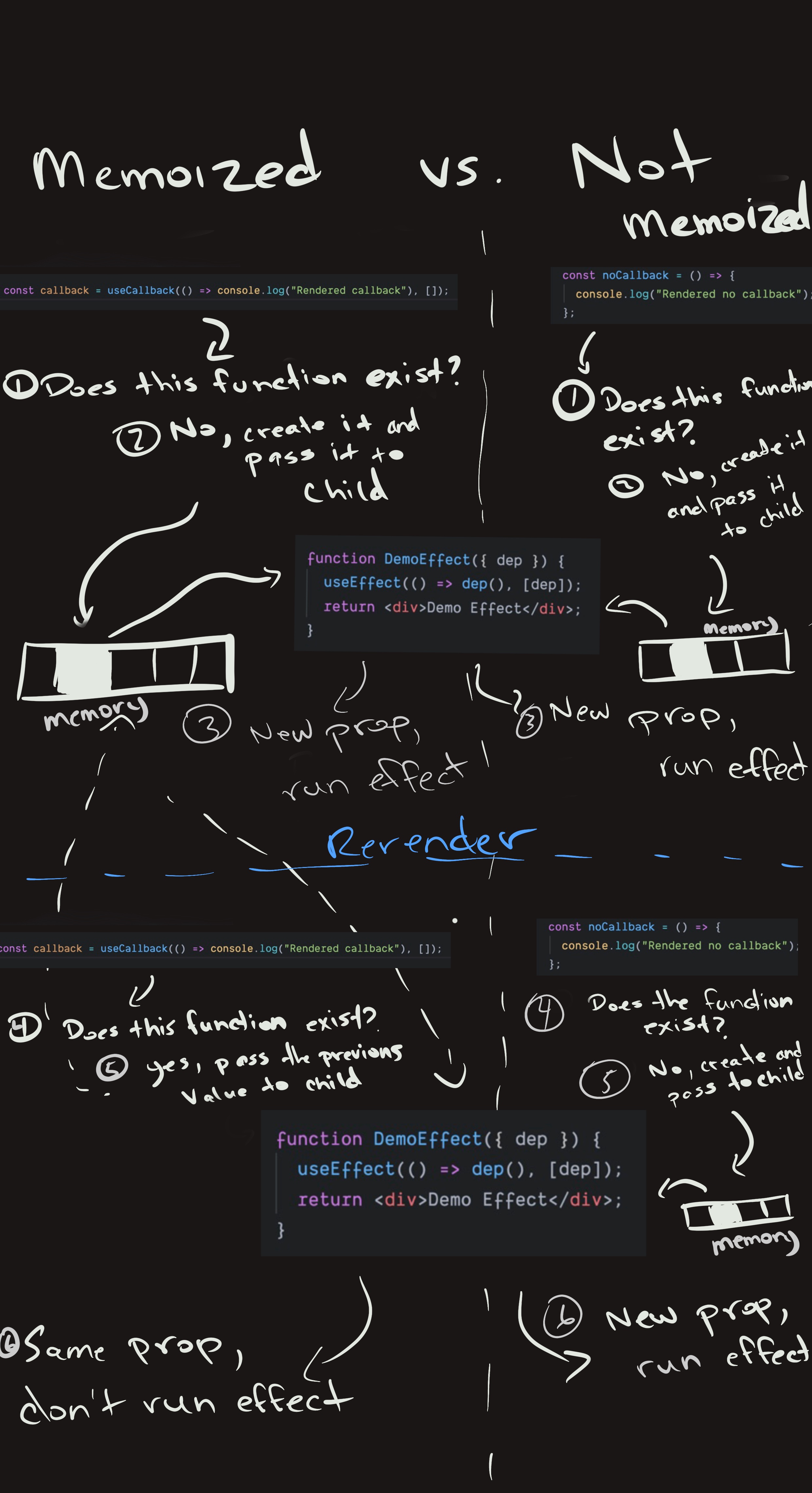

Walking through an example

I helped a friend walk through a code example to better understand how memoized functions work vs. no memoize function by taking a code example and then drawing a diagram along with it. I think it comes across a bit messy without me verbally discussing it at the same time, so I'd like to clean it up and maybe animate it, but until then, I'll post it here in case it is helpful for someone.

The code example can be found here. The code below is what we are going to be walking through; the memoized function is using the useCallback method we describe above, while the notMemoized function is going to be reinitialized every update. Then, both functions are used by the same component (different instances), and there is two renders of the example to give an idea of what happens during an update.

function App() {

const [index, setIndex] = useState(0);

const notMemoized = () => {

console.log("Rendered no callback");

};

const memoized = useCallback(() => console.log("Rendered callback"), []);

return (

<div className="App">

<h1>Hello CodeSandbox</h1>

<h2>Start editing to see some magic happen!</h2>

<DemoEffect dep={notMemoized} />

<DemoEffect dep={memoized} />

<button onClick={() => setIndex(index + 1)}>Rerender</button>

</div>

);

}

function DemoEffect({ dep }) {

useEffect(() => dep(), [dep]);

return <div>Demo Effect</div>;

}

Approach #3: Import the function instead

The last style we can use for our fetchData function actually moves it outside of the component itself. This is a style that isn't often talked about as much as the prior two, but, depending on what it does, can often be my favourite. This style does need for you to use the ESM import style in your modules, and not the CJS style.

Note: Without going too into detail, this is because import statements are going to give us a single instance of a function that cannot be mutated, whereas an exported module with CJS can be mutated. This is also why ESM is statically analyzable. If you do want to read more about this, modules are talked about quite frequently in be Reducing JS Bundle Size series.

In the example above, this could look something like this:

import { fetchData } from './utils';

export function CatFacts({ id }) {

const [data, setData] = useState();

useEffect(() => {

fetchData(id, setData)

}, [id, setData]);

return <div>Cat Fact: {data}</div>;

Because the module cannot be mutated, we don't have to specify the function in our dependency array, as it's not possible for it to change. Now, you can still place the function in the dependency array, but even the ESLint won't force you to do this. So why is this better? Just to avoid putting the function in the dependency array?

The biggest reason I often will split out my functions into utils functions like this is to increase the testability of it. Sometimes I will have some complex logic in my useEffect that I would like to test individually. Now, there are ways to test hooks, but they are a lot more challenging to do. I also find that splitting these chunks of code into named functions increases the readability of my code, so it often is more helpful to do this already, and moving it to a new module gives me better testing for free.

Last, when we do this, it also makes it easier to mock the side effects of that effect when we are doing integration testing of that component. In this example, we've split out the actual async "fetch" side effect. We could mock the fetchData method, and instead, just call the setData argument to be filled with what data we want to test against.

Can you use connect dispatch functions in the dependency array

So now, with all of this background information out of the way, can we finally answer the original question at hand? What if we use a mapDispatchToProps with our useEffect, will it still work? Will it rerender, or do we have to wrap every prop in a useCallback?

No, you don't have to do anything with the mapDispatchToProps, it will work out of the box as we intend it to, just like the useDispatch does. Even the past versions. But why is that?

Well, react-redux has memoized their functions, both in the older code, and also in the new useDispatch hook that was recently released. They've followed the design principals we talked about above and made sure that you don't have to memoize when you get them back. But there are also significant performance benefits to doing this for the previous mapDispatchToProps code. If the react-redux library didn't handle this, users would have to handle this referential equality difference every single time their component updated.

But then why were some users getting issues using the old mapDispatchToProps example. Well, this one took me a little bit to figure out exactly why, but it comes down to ownProps. ownProps is the second argument that is optionally passed to the mapDispatchToProps function call and is the props that are coming in from the parent component.

For more details about this issue, check out more info here

So in this example

function Parent() {

return(<ChildContainer name="Denny" />);

}

function Child({name}) {

return(<div>{name}</div>);

}

const mapStateToProps = state => ({...});

const mapDispatchToProps = (dispatch, ownProps) => ({...});

const childContainer = connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(Child)

If we were to look inside ownProps parameter that is part of our mapDispatchToProps, we would see an object that looked like:

{

name: "denny";

}

Now, our example above is completely contrived as nothing is actually happening. None the less, as long as we have a prop being passed into the Container component, and we have a ownProps arguments in our mapDispatchToProps, that function is going to lose it's referential equality each update. And this makes sense since that object would be a new object every single render. We would have to add extra logic to handle equality checks to determine if the data in the object was the same.

For me, it was easier to think about this problem from the standpoint of a useCallback. If the useCallback was part of our component, we actually trigger a similar problem.

function Component(props) {

useCallback(() => {

fetch(props.url);

}, [props]);

}

Passing the entire prop object is not the way you would typically construct a useCallback, rather than the single values you're looking for. But it has a similar issue, where you are tracking the entire object that is constructed on update rather than the value that is needed. It's always easier to ensure equality in values like strings and integers than it is by comparing memory references or deep comparisons like one could with objects, arrays, or functions.

So I would argue it's harder to hit that issue in useCallbacks, because it's a more unnatural way to structure the code, which is what makes hooks so great as you get more familiar with them. Often, the code style nudges you to a format that is less bug-prone.

In the case of above, I still suggest you use useDispatch if at all possible to avoid these sorts of issues, but if you can't do that, just keep in mind that by using ownProps, you are likely making your code less performant and more bug-prone. A better approach, if you want to continue to use mapDispatchToProps is to pass the needed values through the function, than capturing through ownProps.

Conclusion

I hope you found today's walkthrough valuable and have a better idea of what a useEffect is, and most importantly how the dependency array works. This knowledge works across multiple hooks, so, and is fundamental for building a mental model of functional components.

The most significant piece I hope you walk away with is a more robust understanding of how these values and references need to be handled in a functional component. The goal is to always allow your component to be rendererable and have as much referential integrity as possible. One of the most common issues I've seen with people new to hooks and functional components is a misunderstanding of the dependencies and function references, which cause a super high amount of rerenders or undesirable side effects.

I know a lot of people have been a bit more apprehensive about hooks as a whole, especially moving to the new react-redux hooks, but I've personally found them to make my code more readable, and less bug prone once you are more familiar. I highly suggest the eslint plugin released by the React team as well, as they will help you make the right calls as you get more used to the style.

I'm trying to introduce more visual diagrams to my writeups, and hopefully animate them more and more. I am by no means an illustrator, but in my personal experience, I often find visual queues a lot easier to remember vs. large write-ups. I also have through about supplementing these articles with video explanation/coding for better guidance, so let me know if that's something you would be interested in! If you have any other ideas to help make these more informative or topics you would like to hear about, please leave a comment or contact me at @gitinbit on twitter.

Cheers!