Redux vs. Context vs. State

Over the last year or so, the landscape for state storage in React has seen a tremendous shakeup.

A new implementation of context launched, which is much simpler and straight forward to use. We’ve seen React Hooks released, and, with things like functional states and useReducer, seemingly the option to replace Redux. Not to be left behind, React-Redux has joined the Hooks train and given you a new way to perform state collection and dispatching with useSelector and useDispatch. But are these even needed anymore?

Despite how vocal the community has been on us breaking away from Redux, or state management libraries as a whole, the solution isn’t that simple. We need to break down possible architectural decisions in our applications, then investigate how these tools can support or derail this architecture.

Before we go further, let’s take a step back and some simple questions about our choices:

- What are some state management philosophies?

- Which styles are we covering?

- What are the fundamental differences in their functionality? People have discussed one or the other being a stand-in replacement. But is that really true, behind the scenes?

- What are these tools meant for? Inevitably, the answer we’ll eventually come up with is “it depends.” But let’s try to come up with concrete examples where you might want to employ one tool over the other.

Answering these questions will hopefully give you a strong foundation going forward. Then, when you encounter an issue and need to choose the best tool available, you can make an informed decision.

As the saying goes, a bad workman always blames his tools.

Without further ado, let’s jump in.

State Management Philosophies

Within the last year or two, there’s been a shift in acceptable patterns of React state management. To talk about today, let’s take a little walk through a timeline of React state management to see why we’ve made the decisions we have.

I’ll start with Flux architecture. For many people at the time, Flux architecture was a strong selling point for migrating over from other frameworks.

I remember starting a new job as the only front-end developer on a new project. I had been programming away on it for a couple of months using Angular 1, my old go-to framework, when I saw my first video about flux. That week I stopped and rewrote the project to React. I had used React previously and, I think as a lot of people felt, never really cared for JSX. But seeing this flow, everything made sense.

Soon afterward, Redux came out, and I hopped on the hype train as well. There are quite a lot of ways to use Redux — there’s no “true” accepted pattern. But let’s look at it in the way I believe most people use it.

Note: The examples above show me hopping onto a new code architecture, or a new framework, without much thought. These were successful but, as I’m trying to show in this piece, this isn’t the best response, and it’s something I try to avoid. They worked in these cases, but other times they’ve blown up in my face.

For example, in my first year out of school, I was working at an innovation studio. Somehow, I was in the position of leading a team and found an interesting mobile app “hybrid” framework that employed CSS matrixes to try and get as performant animations as native. Our office was in a battle of native vs hybrid at the time and, being a person who loved web, I convinced my boss we could make solid apps with this framework.

Never mind how unreadable everything in this framework was, because literally everything was through these matrix calculations, I thought it was cool! So we used it for all our new applications, even though the framework was still in Alpha. One day I got an email — the framework I was singing the praises of had suddenly shut down and removed their code from Github. I had to tell my boss that everything needed to be restarted. Ultimately, the projects were cancelled and technology choices were (quite rightly) moved to a senior team member.

The store-own-all era

Redux gave users a central store to store their entire state to, only accessible by the “flux” architecture style. And boy did they save their entire state. For the first year or two, it seemed to be the norm to store absolutely all state data in the store, regardless of what it was.

To match this style of state management, applications were built entirely around the concept of “dumb components” and “smart components/containers.” Dumb components would have no access to any state and were only be visual components. You would have many of these components and your containers would collect the data you needed.

Soon enough, stores turned into unwieldy pieces of data that were impossible to follow and required in-depth knowledge of the code to understand where everything was stored. Furthermore, this rule of “dumb/smart components” was perhaps overused — a lot of codebases ended up in a state where you would only have a single container per page. To fill in that page data, you would often have to prop drill the entire way through, creating an absolute mess to follow. We’re going to call this the store-owns-all era.

Note: I’m not making fun of these, nor discrediting their use today. Most of the issues we come across are from growing teams/codebases. These phases were often community-driven ways to solve these problems.

Feature-owns-data Era

Soon after, there was a push for more code co-location and less dependency on absolutely all code in your store. Often, people moved to styles like domain/feature-based architecture, where a single spot in the store was representative of a feature.

Dumb components still existed, but you would frequently extract those to some sort of global dumb component shared across the codebase, or even an external repo, whose UI framework you could then share.

The store was cleaned up, and designated areas of the application were stored in the properties of the store. These areas may or may not line up to domains or pages. There was also a push to move UI state out of the store and into the components themselves.

To combat prop drilling, there was a trend away from having only a single container at the top level for a page. Instead, a page would contain multiple containers, each housing its feature on the page.

I’m going to avoid getting into the right/wrong of multiple containers vs. a single container. There are upsides and downsides to each.

Also, the new context system (and later Hooks) launched around this time. Interestingly, it didn’t seem like a lot of people moved to use context at the time to avoid prop drilling. This tendency seemed to align with increasing Hooks usage.

I’m sure most patterns popularity can be aligned to famous developers pitching the style. Mostly Dan Abramov.

We’re going to call this phase the features-owns-data era. The store still owned the data and often they were related to a feature set as a whole. The components frequently don’t know how the data got there, or what happens with it, only that it owned that slice of the store.

Component-owns-data era

Which brings us to today, where components own data. This style, which is picking up more and more steam, can be handled by Redux but is more predominantly related to Apollo.

The idea is generally that a component should own its own “lifecycle.” That includes knowing to get data, display loading when it’s not ready, knowing when it needs to recollect data, etc.

There are still one or more stores, but it should be smart enough to know which data is related to one another. Do two different components need the same data? They can share it, but they both know how to collect that data as well. If one of the components collects new data, that will update the other as well.

This style is complimented well by a lot of recent and upcoming initiatives by the react team, such as suspense, both for data fetching and for component initialization. It removes this idea of “did someone collect my data yet,” and instead, the component can confidently render itself.

Component ownership also compliments the idea of concurrent mode too, which gives more control of the component’s lifecycle to the component itself. If you have not tried something like Apollo out, I highly encourage it. It is challenging to move away from the more classic styles, but I find the system more durable, especially for larger teams. Someone doesn’t need to know your components/containers, and the structure of your redux store, and other dependencies, to understand how they can use it. Instead, they can trust your component will always handle itself.

With that being said, this article is not going to be going into the components-own-data phase. This is a relatively deep topic — that talk can be saved for another day. I highly encourage anyone interested to check it out. I also want to demystify the differences between redux and context, and adding Apollo to the mix will add too much noise, without enough investigation.

The questions we highlighted at the start of this piece are still foundational to the first two phases (and can be used in the third) and I want to examine the them further. I think most small-to-medium size applications rely on the store-owns-all and features-own-data strategies, so we should understand what we’re doing and what to watch out for.

State Management Styles

With the philosophy out of the way, let’s jump into the functions we’ll cover:

- Component state

- Instance variables and mutatable refs

- Context

- React-Redux using Connect/Hooks

There are many more options out there, including the popular libraries Mobx and Apollo (as mentioned earlier). I’m going to stick to these, though, as most of them share enough similarities to Redux that the knowledge is transferable.

Component State

Let start with the basics: component state. In this piece, we’ll frequently be using the function state with Hooks, but this information can be shared with class components as well.

A components state is declared by using the useState Hook, which stores data within the given component and persists throughout renders. This state is not mutable, meaning that if you try to set it, it will not update. To update that state, you must use the setState function returned while initializing.

import React, { useState } from "react";

function Header(props) {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("Title");

}

The above code block demonstrates basic usage of the useState hook

So what’s the difference between using a state variable and using a local variable? The state variable is intrinsically tied to the lifecycle of the component; while local variables, on the other hand, will reinitialize — each time the function is executed, the state will maintain.

Note: If you use a class component, instance variables persist through a re-render. More on that later.

A pronounced difference between local variables and states is that changing any state will cause the function to execute again. Local variables, and the upcoming mutatable ref variables, will not trigger this re-render. Therefore, if you update a local variable with a new value, and that value should be output in the JSX, the change won’t be visible.

It’s important to note that even after we change our state, the value of the state variable won’t update until the next running of our function. That’s because the component won’t immediately stop and rerun itself, which would cause a memory leak. Let’s take a closer look at this in action:

import React, { useState } from “react”;

export default function App() {

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(1);

const onClick = () => {

setCounter(counter + 1);

console.log(counter);

};

return (

<div className=“App”>

<h1>Hello CodeSandbox</h1>

<h2>Start editing to see some magic happen!</h2>

{counter}

<button onClick={onClick}>Increment</button>

</div>

);

}

// Clicking the button will display 2, but log 1

Each time you click the button, the screen will show one number higher than what your console logs out. Why is this important? This should give you an idea of how the state works behind the scenes with the react component. It’s directly tied to the lifecycle or current “state” of your React component.

Although React state can be used for data storage, doing this in medium or larger applications can cause your code to be more unwieldy and harder to understand.

Instance Variables and Mutatable Refs

Despite the complex names, these are both the same thing. Or at least they serve the same purpose. Let’s take a quick look at a class component with an instance variable, as I believe they’re easier to understand at a glance.

import React, { Component } from “react”;

import “./styles.css”;

export default class App extends Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.instanceCounter = 1;

this.state = {

stateCounter: 1

};

}

setStateCounter = () => {

this.setState({

stateCounter: this.state.stateCounter + 1

});

console.log(this.state.stateCounter);

};

setInstanceCounter = () => {

this.instanceCounter = this.instanceCounter + 1;

console.log(this.instanceCounter);

};

render() {

return (

<div className=“App”>

<h1>Hello CodeSandbox</h1>

<h2>Start editing to see some magic happen!</h2>

<div>

State Counter: {this.state.stateCounter}{“ “}

<button onClick={this.setStateCounter}>

Inc State

</button>

</div>

<div>

Instance Counter: {this.instanceCounter}

<button onClick={this.setInstanceCounter}>

Inc Instance

</button>

</div>

</div>

);

}

}

In the demo above, we’ve created a variable for the class. It will reside with only that single instantiation of the class (hence the “instance” variable). If you click the Inc Instance button, the difference with the state variables should become apparent. It did not update visually. That’s because instance variables are not tied directly to the lifecycle of a component, and cannot cause the component to re-render.

A components current visual state is a mixture of the current internal state and props of a given component

That’s not to say other things can’t become a factor, and instance variables are an example of one of these factors. A good rule of thumb is to avoid these external factors as best as you can. The more external factors you add to a given component, the less predictable and pure your component becomes. This is a breeding ground for bugs and code that’s challenging to reason about.

Now, back to the example above, if you examine the logs while clicking the instance button, you’ll notice the correct number for where we should be at is displaying. So the data is storing correctly, and if we click the Inc State button, we actually will see that, given a re-render, that data is now correctly displaying.

Now, there are some rare cases that this is useful. Let’s come back around to these in our next section.

As we said earlier, instance variables are not a thing in functional components. That’s because each time the component is rendered, those variables are reinitialized. Given that, there’s a mechanism that allows this functionality — useRef. Of course, useRef typically serves the purpose of attaching to a DOM element, but we can also use it for creating mutable values that can exist through renders. Check out the Hooks API Reference – React for more information.

Context

Here’s where things start to get interesting. Context is a mechanism designed to store data, and alert consumers when that data has changed. This kind of sounds like state, but isn’t quite the same. Context doesn’t have any rules around telling the Provider component itself when a change has occurred. Rather, its mechanism is to instruct consumers when it notices the provider’s value has changed.

Using context can be confusing to read and understand at first. So let’s jump into some examples.

let contextData = “hello”;

function onChange() {

contextData = “goodbye”;

console.log(contextData);

}

const Context = React.createContext(contextData);

function LevelOne() {

return (

<Context.Provider value={contextData}>

<LevelTwo />

</Context.Provider>

);

}

function LevelTwo() {

return <LevelThree />;

}

function LevelThree() {

const context = useContext(Context);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={onChange}>

Change context

</button>

{context}

</div>

);

}

The first example is a simple context, not using any state. We provide data to the context, which is used in our LevelOne component as a provider, and our LevelThree component as a consumer. The data is displayed there correctly and outlines a good use case of this style of context — some sort of static data that is passed throughout our components.

But what if you want this data to be dynamic and change? You’ll notice that the button in our example is set up to change the context data object — however, clicking the button changes the data, but doesn’t change the context on-page.

Now, if you’re used to React or Javascript, it’s probably apparent to you that changing this data won’t change our context value. That code only runs on the initialization of the module. But if you start walking through the steps to include that within the component lifecycle, you will inevitably begin to use state. And that’s important.

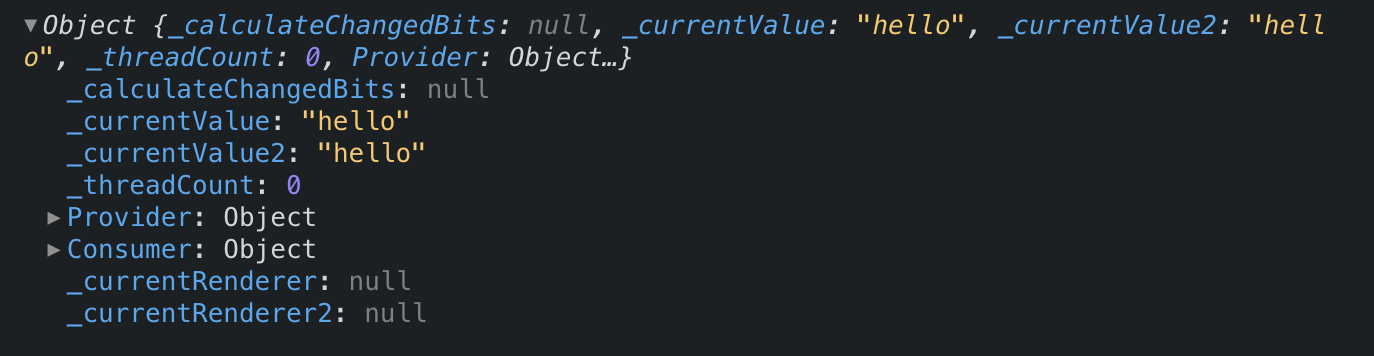

Take a look at the Context object itself and you will see there are no public functions to update our values:

That’s because, although the context object’s primary purpose is the mechanism to update consumers on the provider’s value change, it does not provide tools to re-render the component that houses the provider. Instead, it’s similar to a Pub/Sub pattern that informs its subscribers when the value has changed.

We need a different tool to store the data and inform our component to re-render when that data changes. React already provides us with that tool, state.

Building on the foundation we covered earlier, to control the Provider’s lifecycle, we need to tie in state. Let’s see how to do that with an example.

Again, technically we can use instance variables, but this would be an odd choice with

_context_since it would need to wait for a different event (state or parent) to re-render and notify the consumers of this change.

const Context = React.createContext();

function LevelOne() {

const [contextData, setContextData] = useState(“hello”);

return (

<Context.Provider value={{ contextData, setContextData }}>

<LevelTwo />

</Context.Provider>

);

}

function LevelTwo() {

return <LevelThree />;

}

function LevelThree() {

const { contextData, setContextData } = useContext(Context);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setContextData(“goodbye”)}>

Change context

</button>

{contextData}

</div>

);

}

Notice that we are now storing the data in our LevelOne state. That data and its setter are placed into the Context provider’s value. Now, when we click the button, the following events will occur:

- Update the state value of Level one with

goodbye. - Cause a re-render of

LevelOnecomponent. - The re-rendered

LevelOnecomponent now passes the valuegoodbyeand its setter, into theProvider. LevelTwois re-rendered.LevelThreeis re-rendered. When the value is pulled from the context, it now reads asgoodbye.

Note: This isn’t precisely how Reacts rendering order works, but it serves our purpose.

If you’re new to Context, you may wonder why you would ever use it, as you could simply pass the values as props. That’s a question we’re going to come back to later, but let’s look at one more example that displays the power of context.

const Context = React.createContext();

let levelOneCalls = 0;

let levelTwoCalls = 0;

let levelThreeCalls = 0;

function LevelOne() {

const [contextData, setContextData] = useState(“hello”);

console.log(`Level One calls: ${++levelOneCalls}`);

return (

<Context.Provider value={{ contextData, setContextData }}>

<MemoLevelTwo />

</Context.Provider>

);

}

function LevelTwo() {

console.log(`Level Two calls: ${++levelTwoCalls}`);

return <MemoLevelThree />;

}

const MemoLevelTwo = React.memo(LevelTwo);

function LevelThree() {

console.log(`Level three calls: ${++levelThreeCalls}`);

const { contextData, setContextData } = useContext(Context);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setContextData(“goodbye”)}>

Change context

</button>

{contextData}

</div>

);

}

const MemoLevelThree = React.memo(LevelThree);

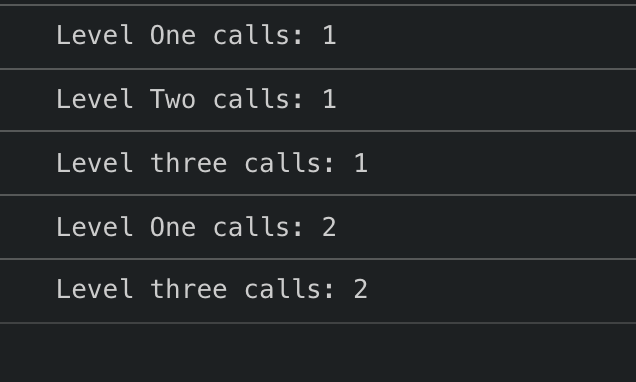

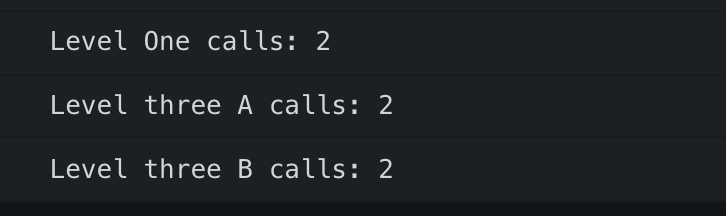

In this example, we’ve memoized our components and added a console.log to print when that component is re-rendered. If you try the case, you’ll see each component executed precisely once. Now click the “Change context” button and you will see that only Level One and Level three were called.

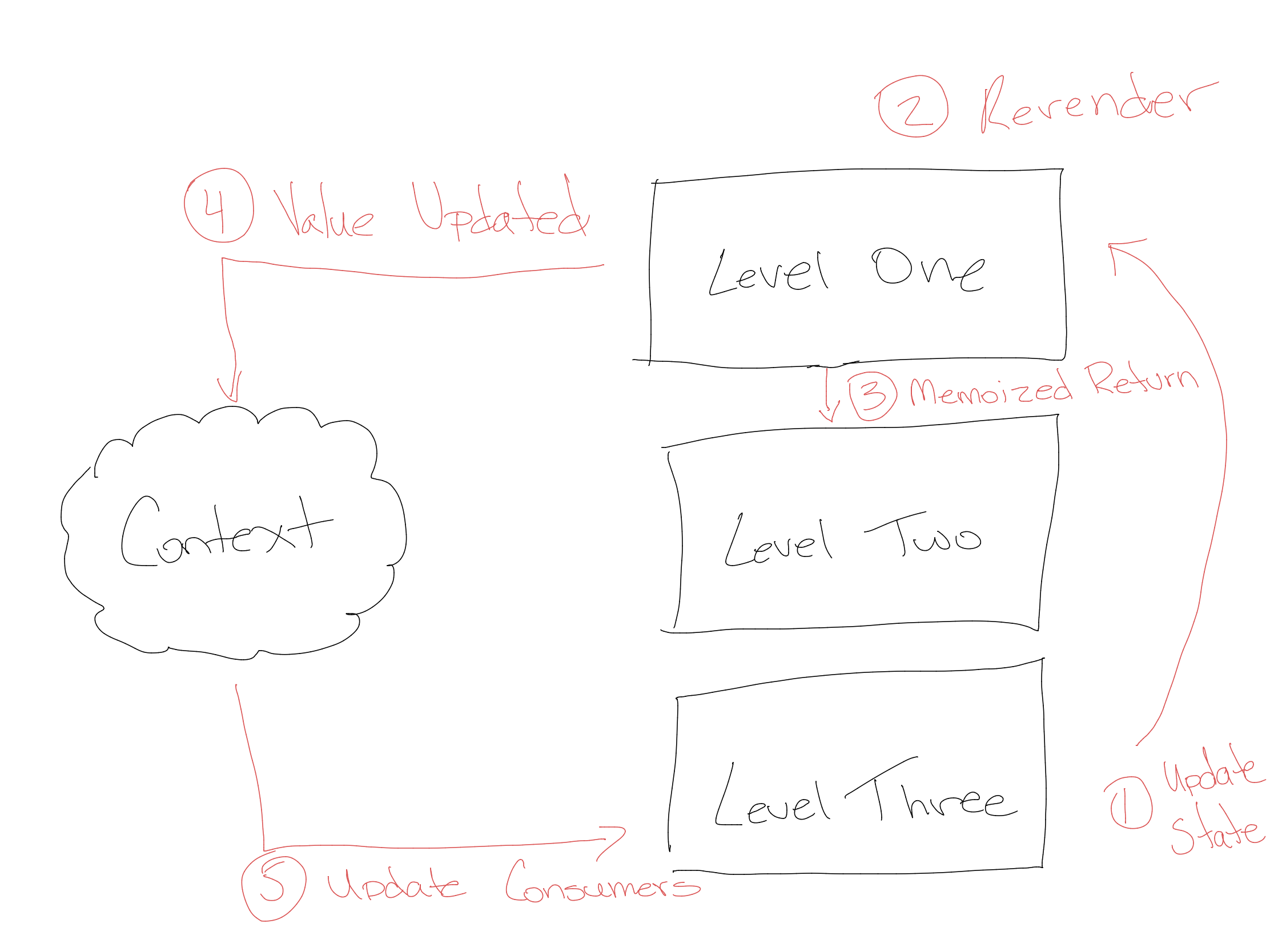

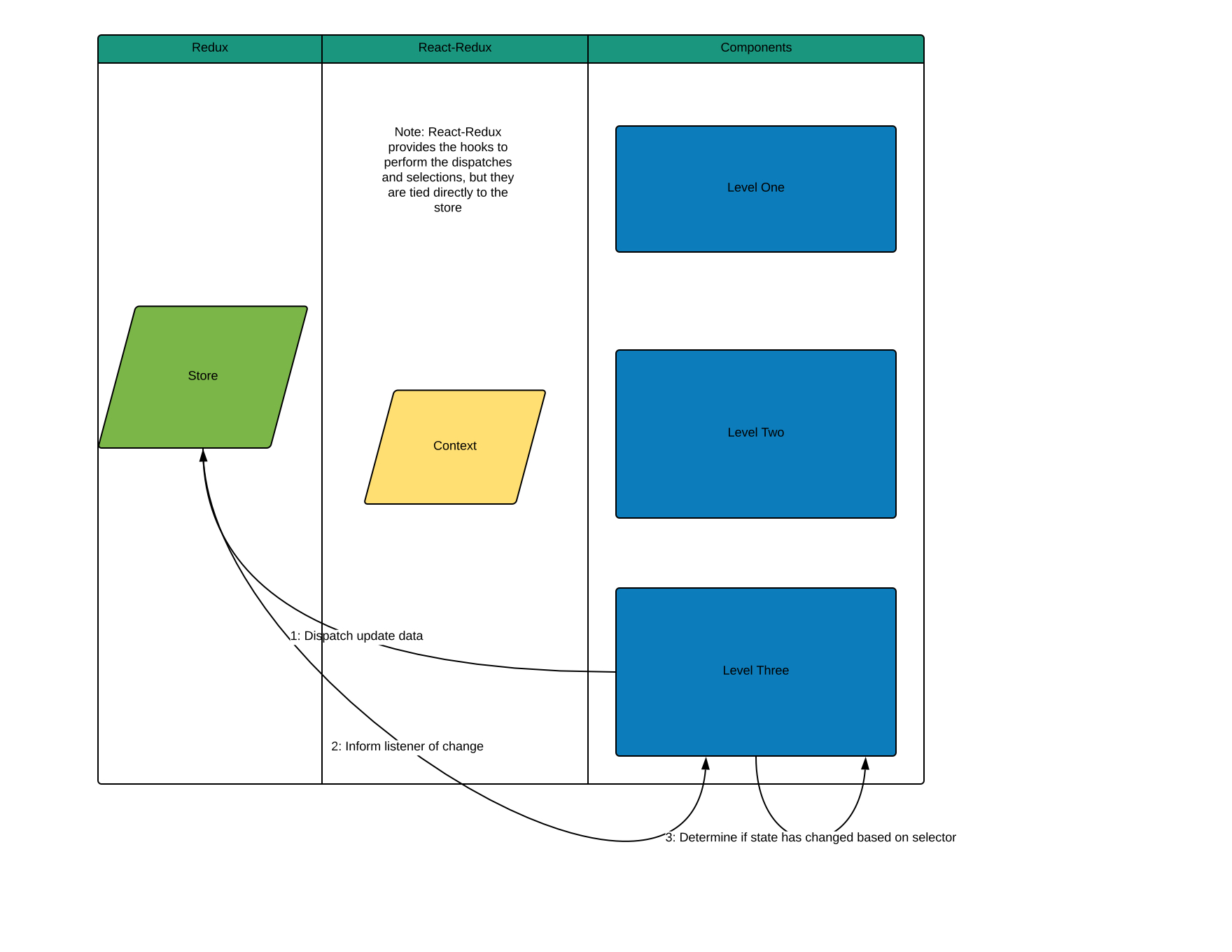

So what does this mean? It demonstrates the Pub/Sub-like pattern that the Context system employs. Let’s draw a picture to walk through these events.

Let’s follow the chain of events in the above picture. A user has clicked on the button to update the context data. The context itself will notify all its consumers if that data has changed. There’s no need for us to re-render level two since none of that has changed.

This is a rather trivial example, but you can imagine for deeply nested components, this can be rather handy. This is where the idea for “replacing Redux” has come from. We will return to this!

React-Redux Connect / useSelector

To get a better idea of this system, let’s dive into some of the innards of Redux and how React-Redux uses them.

What is Redux?

Redux is a state container for JavaScript applications. Although it was initially built for use with React, it’s not tied to React. Instead, we use a library from the same team called React-Redux to connect Redux to React.

The actual structure and shape of a Redux store are entirely up to the user. It must fit the same shape as the original passed in state, which they refer to as Preloaded State. Traditionally, this is an object and is placed into the variable [currentState](https://github.com/reduxjs/redux/blob/master/src/createStore.ts#L133). At this point, nothing complex is happening, and we just have a single variable that stores our data. Now we want to turn this into a pub-sub.

The PubSub pattern is a form of an observer pattern where users can “publish” updates to a central system, and any subscribers listening to those events are updated accordingly.

So what do these steps look like in our system? Let’s look at the events in sequential order:

- An event takes place in the system, which dispatches an action to the store.

- The store takes that action and updates the store through state reduction.

- Once the store has updated, we inform all listeners to the store that the data has changed.

Note: If any new subscriptions are added after one has occurred, they will not be notified of a change within the system while iterating through the listeners. After the update is complete at #3, we then move any new subscriptions into our [currentSubscriptions](https://github.com/reduxjs/redux/blob/master/src/createStore.ts##L250).

So, who are the listeners? In the case of Redux, they are any entity that has subscribed to it. You may have seen the syntax for it before, but it happens after you create the store:

const store = createStore(reducer);

store.subscribe(() => console.log(‘called each change’));

Middleware is built using this API, as well as React-Redux. Again, it’s not React specific — absolutely anything can tie into this pub-sub and know about state changes.

One thing you might notice here is that absolutely every single change to the store will call our subscribed event. Does this happen under the hood of our React components? Wouldn’t that be heavy, as each component will be updated no matter the change? Well, this is an excellent opportunity to dive into React-Redux!

What is React-Redux?

React-Redux is a binding library used to connect React to Redux. That’s not all it does though; it also gives us several enhancements under the hood that are often overlooked. Before we look at these enhancements, let’s see how it connects the Redux pub-sub to our components. This can be done in one of two ways: with the traditional Connect syntax or with the newer useSelector and useDispatch hooks.

First, let’s talk about their similarities. Both of these approaches use the React Context system to pass the store instance to any child components in the react tree. Note that this isn’t the store state itself — this is collected later.

Beyond that, there are a couple of misconceptions about how Context is used in React-Redux. We saw earlier that the Context system does have a mechanism to inform child components that our values have updated. But React-Redux does not use this mechanism. Instead, they subscribe directly to the store itself and use the store pub-sub to be notified of possible state changes. This is the store.subscribe() that we mentioned earlier.

useIsomorphicLayoutEffect(() => {

function checkForUpdates() {

try {

const newSelectedState = latestSelector.current(store.getState())

if (equalityFn(newSelectedState, latestSelectedState.current)) {

return

}

latestSelectedState.current = newSelectedState

} catch (err) {

latestSubscriptionCallbackError.current = err

}

forceRender({})

}

subscription.onStateChange = checkForUpdates

subscription.trySubscribe()

checkForUpdates()

return () => subscription.tryUnsubscribe()

}, [store, subscription])

return selectedState

}

Note: This is the

_useSelector_example. The subscription logic for_connect_is very similar, and can be found here.

When the store state changes, it will call checkForUpdates, which determines if the state alteration has any effect on this component. If it does, it calls forceRender, re-rendering this component. In this entire flow, the Context is never used. So what’s the purpose of it?

A special thanks to Mark Erikson, who helped me walk through the React-Redux/Context approach. He wrote a fantastic post here that goes more in-depth on these reasons.

The purpose of Context within this system is to do exactly as we said above. We use the Context provider to tell React where this store is housed in the hierarchy of the React tree. Any child components of that provider have access to that store instance. This gives us the ability to have multiple stores, nested stores, and a cleaner approach to passing the store instance.

Why doesn’t React-Redux use Context to update the child components? There’s a Github Issue outlining the reasons, but I want to look at a purpose that we’ve already described in this post. Remember the context example we used before? We were able to reduce the amount of re-renders in our system to two. They were:

- Re-render the component house the provider, to update the value

- Re-render any components housing a consumer.

LevelTwo (the component with nether provider nor consumer) was not re-rendered because it was memoized and had no changed props that would need to update the component.

That means, for any children of the provider, and any children of the consumers, your components should be memoized so as to reduce unnecessary re-renders — particularly children that do not require props from said state updates.

Now, I’m not arguing against memoization. Memoization is a crucial tool in your belt, that is under-utilized and often misunderstood (perhaps an article on that next). But that’s a pretty hefty requirement to your components and any future components.

There’s also one other issue we come across that I left purposely vague in our list above.

Render any components that house a consumer.

In the example above, we only have a single consumer, and therefore don’t see the full extent of what this means. Let’s build a case with two components with consumers instead.

const Context = React.createContext();

let levelOneCalls = 0;

let levelTwoCalls = 0;

let levelThreeACalls = 0;

let levelThreeBCalls = 0;

function LevelOne() {

const [contextData, setContextData] = useState({

levelAData: “hello”,

levelBData: “Tobias”

});

console.log(`Level One calls: ${++levelOneCalls}`);

return (

<Context.Provider value={{ contextData, setContextData }}>

<MemoLevelTwo />

</Context.Provider>

);

}

function LevelTwo() {

console.log(`Level Two calls: ${++levelTwoCalls}`);

return (

<div>

<MemoLevelThreeA />

<MemoLevelThreeB />

</div>

);

}

const MemoLevelTwo = React.memo(LevelTwo);

function LevelThreeA() {

console.log(`Level three A calls: ${++levelThreeACalls}`);

const { contextData, setContextData } = useContext(Context);

return (

<div>

<button

onClick={() =>

setContextData({

…contextData,

levelAData: “goodbye”

})

}

>

Change context

</button>

{contextData.levelAData}

</div>

);

}

const MemoLevelThreeA = React.memo(LevelThreeA);

function LevelThreeB() {

console.log(`Level three B calls: ${++levelThreeBCalls}`);

const { contextData, setContextData } = useContext(Context);

return (

<div>

<button

onClick={() => setContextData({

…contextData,

levelBData: “funke”

})}

>

Change context

</button>

{contextData.levelBData}

</div>

);

}

const MemoLevelThreeB = React.memo(LevelThreeB);

So, we’ve updated our context to have two consumers, and both of those components are being displayed at a sibling level in LevelTwo. Now, when you click either of the buttons to update one of their states, you should see this:

No matter what, both of these components are re-rendered, despite them both being memoized, and at a sibling level. That’s because context only notifies their consumers that a change has occurred. It does not know whether that change affects the component using that consumer.

As our application grows, this problem also grows. There are strategies around this, which we will get more into later, but this is why React-Redux does not use context to update its components. Instead, React-Redux relies on its internal pub-sub to notify children.

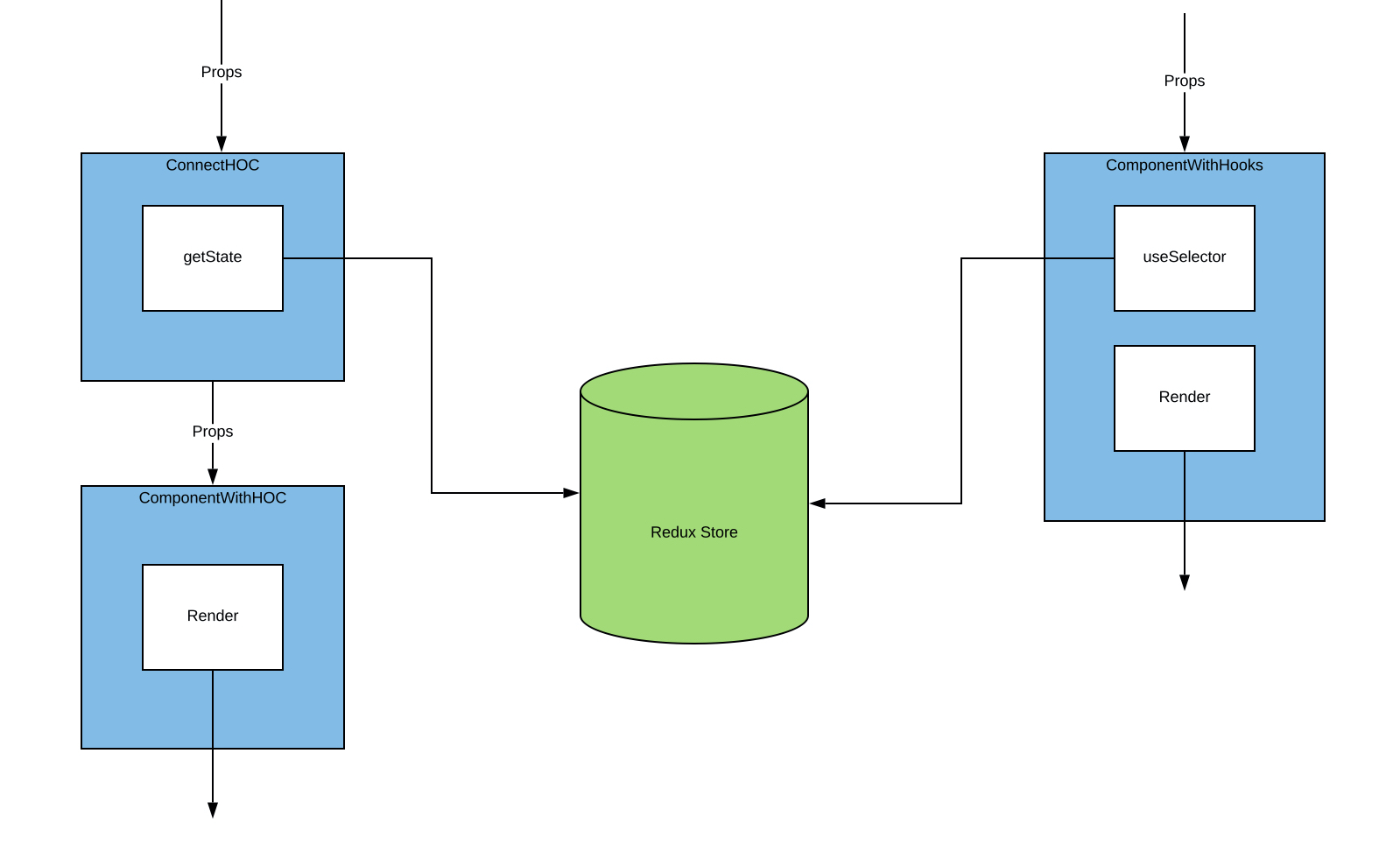

So how do the re-renders look when we use React-Redux? Let’s start with a code example, then walk through a diagram to explain the steps.

This example will still be using

_useSelector_, but subscription-style is similar to_connect_.

let levelOneCalls = 0;

let levelTwoCalls = 0;

let levelThreeCalls = 0;

function LevelOne() {

console.log(`Level One calls: ${++levelOneCalls}`);

return (

<Provider store={store}>

<LevelTwo />

</Provider>

);

}

function LevelTwo() {

console.log(`Level Two calls: ${++levelTwoCalls}`);

return <LevelThree />;

}

function LevelThree() {

console.log(`Level three calls: ${++levelThreeCalls}`);

const contextData = useSelector(state => state.data);

const dispatch = useDispatch();

const setContextData = data => dispatch(updateData(data));

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setContextData(“goodbye”)}>

Change context

</button>

{contextData}

</div>

);

}

Here’s our code now using a Redux store, connected through the React-Redux provider and Hooks. Note that there is some additional boilerplate, like the reducer and actions, that isn’t present here. You can check out the code example above to see more.

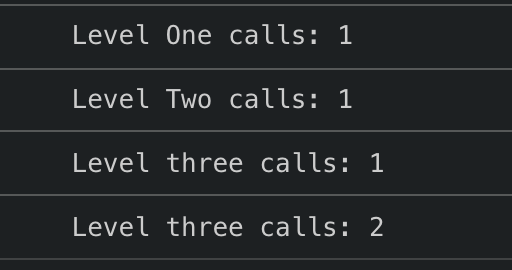

What happens now when we click the Change context button? Our output should look like this:

Each component was called once for the initial render. Now, when we update our Level Three component, it only re-renders that single component. Not even our provider component updates.

And you will see that if I split our tree into two LevelThree components, like our last example, only a single one would update (assuming they were different state values). How is that?

Partly because of the Redux subscriptions. But you might recall from the Redux breakdown above, a subscription gets called for every single change in the store. And that does happen here, but React-Redux gives us more under-the-hood tools to help increase performance. Here are the steps it takes:

- A state update is published.

- All the listeners, in this case, every single rendered component using

useSelector,will call theircheckForUpdatesfunction. - Each component takes the store instance passed to them from the context earlier, to get the current state of the store.

- Use the selector passed in to derive a new state value for this component.

- If the new derived state used by this component has changed from before, re-render the component. If not, do nothing.

This flow can be seen here:

const newSelectedState = latestSelector.current(store.getState());

if (equalityFn(newSelectedState, latestSelectedState.current)) {

return;

}

forceRender({});

Note: That equality check is where connect and

_useSelector_start to have some differences. We’ll dive into those in a moment. At a high level though, these work similarly.

An even more simplified version is broken down in this diagram:

Note, any child of component three will also still be re-rendered, so, if that’s not desirable, it’s still on the developer to ensure that child components are properly memoized.

Differences between mapStateToProps and useSelector

Although the general idea of useSelector and mapStateToProps are the same, there are some key differences under the hood that can throw you for a loop if you’re not ready for them. However, in my experience these differences, or at least their significance to us developers using these tools, have been greatly exaggerated

To help break down the differences we first need a high-level understanding of what the structure of each approach is. Once we know the difference in architecture, the difference in style should be clearer. So first, let’s examine each signature.

function ComponentWithHook() {

const user = useSelector((state) => state.user);

const color = useSelector((state) => state.color);

const location = useSelector((state) => state.user.location);

return (

<div>

<div>Color : {color}</div>

User: {user.name}

<Location city={location.city} country={location.country} />

</div>

);

}

Note: we are going to be doing some selectors that I wouldn’t typically build. This is to try and examine the differences between styles.

Above is the Hook style, using the useSelector Hook of react-redux. Now let’s take a look at the classic mapStateToProps.

function ComponentUsingHOC({ user, color, location }) {

return (

<div>

<div>Color : {color}</div>

User: {user.name}

<Location city={location.city} country={location.country} />

</div>

);

}

const mapStateToProps = (state) => ({

user: state.user,

color: state.color,

location: state.user.location,

});

const ComponentWithHOC = connect(mapStateToProps)(ComponentUsingHOC);

As we can see above, the Hook can tie directly into the data and pull out what’s needed. On the other hand, our HOC requires us to create a mapStateToProps function and pass it into our HOC, along with the eventual component. That component will then receive all state data as props.

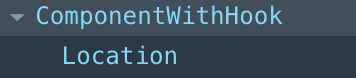

The DOM output is the same, but there is a difference in the structure of our React document.

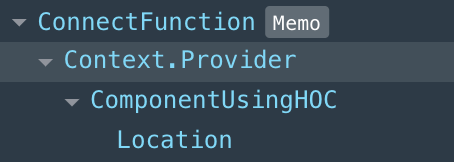

ComponentWithHOC React Structure

It appears that our Hook component resembles precisely the elements as they appear in our code. The connect HOC component is a little bit more complicated. Now, we know connect is a HOC, and if you’ve previously used HOC’s, you should have some idea how this looks, but let’s diagram it.

Now we have this extra component that wraps our component. This is responsible for collecting the state data and passing it to our component as a prop. Now, because our component is wrapped with this higher-level component, some extra optimizations are performed out-of-the-box, which aren’t available for Hooks. Namely, we can render both the component creation as well as memoize our actual connect HOC.

What does that mean for people using or migrating to Hooks? It means that where you previously had “free” memoization caused by the connect HOC you will now have to handle on your own. For most cases, that’s as simple as wrapping your component in a React.memo.

There’s also a difference in how equality is compared. Previously, the connect used a shallow equality check to determine if changes had occurred, whereas useSelector uses a strict equality check. This may sound like a more significant change than you might expect, but you can see in the example above that it doesn’t affect as much as you might think. With proper memoization to avoid re-renders, you’re probably fine. If you need a more strict equality check, the second argument to useSelector does let you specify the equality check.

So which should I use?

So which solution should you use? As I said at the start, the obvious answer is going to be “it depends.” But what does it depend on? Well, the truth is, you should use all of them. The idea of using one is going to stunt your application more than help it.

Let’s quickly look at each of them.

React state

This should still be used for your UI state. Unless your UI state is necessary to know globally, I highly encourage you to house that data here. For those that don’t know UI state, it’s something like, “is that popover open?”

If it doesn’t make sense to place the state in the component itself, it probably makes sense to place it in the parent. Putting too much UI state in your store makes it confusing and hard to follow. Furthermore, it tells the other developers on your team that there are probably other things dependent on that state, making your code harder to use.

That being said, if your application is small enough, React state is probably more than enough to handle your use case. There are new tools that can make this easier on you, like useReducer, but just be aware of our tests earlier. If your application begins to scale, redux (or other state management libraries) will help that code scale as well, and aid you on performance and debugging.

useRef and instance variables

This one is a handy tool that I don’t think is known enough. That’s not to say you should be going for it immediately, as a mutable state is pandora’s box of bugs. But if you have some sort of data that needs storing and is used central to that component, but you don’t want a re-render from it, it can be a trick that comes in handy.

Oddly, one place I’ve come across it is in using old libraries. Perhaps we need to remember that a library has been called and is open somewhere on the page (think an old popper popup). This is a great way to have access across renders, but to not change the actual element itself. I’ve also seen it for data passing in through effects, where there can be renders from other values, but the passed value should not trigger a re-render.

Again, be careful with these, but they’re handy to have in your back pocket. That being said — never use it as actual state management.

Context

I think Sebastian Markbage (one of the react devs) said it best:

My personal summary is that new context is ready to be used for low frequency unlikely updates (like locale/theme). It’s also good to use it in the same way as old context was used. I.e. for static values and then propagate updates through subscriptions. It’s not ready to be used as a replacement for all Flux-like state propagation.

That being said, I’ve seen several places say, “we are using Redux, so we should never use Context.” I don’t necessarily agree with that if you’re using context correctly. I think context should be generally used for static data that is passed throughout the application, such as for theming, and it’s particularly good at that. It doesn’t pollute the store and is very simple to collect.

If you are interested in seeing how you can use Redux to do some of these, I did create a simple react auth tutorial using context. I don’t recommend using this for a production application, but it could be interesting to you.

Redux

I think Redux is still incredibly useful. There are other great tools out there, and I’ve personally moved to use Apollo more and more, but Redux is the first thing I grab when my application gets to a point where I feel state management is needed, or I’m not using graphQL.

Redux is incredibly easy to read and, although the boilerplate can be annoying, as you use Apollo more, you’ll pine some days for the ability to see “all the magic.”

I’ve moved a couple of applications away from Redux, to using state and context, as I became curious if there would be noticeable gains. Again, there’s a decent loss to boilerplate. This is more noticeable in smaller applications, where redux boilerplate can take up a larger portion of the codebase.

Shortly after migrating some of these projects, I had other developers come onto the team and use the application. They were able to deduce how the system worked, but we noticed that there was a larger amount of renders than our systems would normally handle. We didn’t have a strong handle on how context’s pub-sub differed from Redux’s. That investigation eventually led to the learnings here.

Furthermore, we had issues come up that we weren’t able to properly debug as we were used to. That's because great tools like Redux and Apollo have amazing dev tools to help you. Once you miss things like simple state inspection, time travel, and dispatches, it’s going to become more frustrating.

That's also not even accounting for middleware. There’s an entire suite of libraries at your disposal that can hook into your Redux middleware, and you’ll find you miss those pretty quickly. We wanted to just hook into the actions happening in our application, but without Redux, we had to tie it more directly to the component itself.

My honest feeling is that, outside a small application, the issues people have with Redux are related more to how they are using it than the tool itself. Are you still using it where the store owns everything? Can you migrate to a more domain, feature-owns-data structure? Even more, can you attempt a component-owns-data structure? These are questions we need to ask ourselves. Again, as the saying goes, the bad workman always blames his tools.

As I said above, my habit is to use a tool like Redux or Apollo for my data management, my React state handles local information, often UI state, and context handles static data, such as theming. I see no problem having these tools used together where each has its own strength.

What about one source of truth?

That’s a vernacular that's thrown out a lot when you start employing these different tools in tandem with one another. “You should only have a single source of truth!”

But that’s not what this phrase is about. The intention is that for a single piece of data, you should only have a single source it comes from — the true “data.” The saying is also true, even for a single store. You should not have multiple areas of your Redux store containing the same data, as you’ll end up following out of sync somewhere, and making your codebase a lot harder to understand.

For a simple example, think about a prop coming into a component. It’s pretty discouraged to then tie that prop to your state, like so:

function MyComponent({username}) {

const [user, setUser] = useState(username);

return (...)

}

Can it be done for good reasons? Yes, of course. But you’ve now created two sources of truth for this element, the state, and the prop. If you’re putting that value into the React state, you’re probably going to use that version. But what happens if the prop updates? Or when the state remounts? You can handle these edge cases, but it makes your code more bug-prone, and tougher to reason about.

function MyComponent({username}) {

const [isOpen, setOpen] = useState(false);

return (...)

}

On the other hand, in this example, we have two sources of truth. One is the internal state, and the other is a prop. That’s totally fine and probably something you do all the time. But if you look at each piece of data, they successfully have a single source of truth.

So I’m fine with multiple stores of data. I’ve even seen many successful uses of multiple Redux stores, often used as a “per page” Redux store. This sort of thing actually made debugging a lot easier per page, as you only had relevant info in your store.

You, of course, want to balance this all with making sure your code is easy to understand, but don’t avoid one of these tools just because you’re trying to follow a rule that’s targeting a different problem.

When shouldn't I use a state management library?

The short answer here is with a small application. That’s still a choice you can make yourself, as Redux is rather tiny, but it does complicate your code if you have a couple of simple pages with nothing more.

Let’s try and understand more by going by application size.

Small application

If you’re listening to tutorials online, the answer here would appear to be context. There has been a pretty vocal chunk of the community pitching to move away from redux, and instead handle state through context.

As we’ve talked about above, I would encourage you not to do this.

In a small application, this is possible to do, but as we saw with our tests, this can scale out of control pretty quickly. It can be enticing to move away from the Redux boilerplate, but you’ll find that sooner or later the boilerplate is handier to have.

Also, although passing props can get a bad name now, don’t undervalue it. Passing props is the API to your component, and the more you can put to your API, the more reusable that component can be. That’s not to say you shouldn’t use other means, but rather, don’t try to force a square peg through a round hole. If you have an element with one or two levels of children, it’s still a sensible structure to pass those children.

Also, if you’re genuinely having troubles with deep prop drilling, none of the solutions above are likely the answer to the problem — you need a workaround. It’s likely that you have too many components and need to introduce better composability to your code. I would highly encourage you to check out Material UI’s codebase or check out this video by Micahel Jackson.

Medium and large applications

I really can group these into two because the answer is evident here. Context should not be your solution here and I would highly encourage you to use a state management system.

I find that it is in medium applications that more significant architectural questions come into play. At this point, you should either be examining a stronger “domain” driven style using Redux or beginning to look at components owning data. You can do this with React, but Apollo would be the first place I nudge you to read about this style. They have fantastic docs and articles, so please check it out.

Conclusion

This was a rather large article to end up where we started, but I hope by passing through them, you no longer think about these state management styles as different choices, but as a plethora of tools. They each have benefits that can and should be used together.

It’s your job as a developer to understand where each one is strong and weak. These tools should not be a “choose one and forget the rest”, but each should be a tool in your belt. Then, when someone tells you “x tool is bad”, you can try to help them understand where that tool truly shines.

You want to make not only a great feature but also write code that is both readable and understandable. Developers should be able to come to your code and, by seeing what you used, quickly determine how the system works as a whole.

These will often be assumptions, but if someone can read your code at a glance and assume correctly how the system works, you’ve done a fantastic job!

Thanks for reading today!