Object Oriented Javascript: What it is, and when to use it

Let's talk about Object Oriented Javascript. As with everything in Javascript, there is many ways to architect object orientation. The following is my best practice. It's the collective sum of opinions between different developers at my workplace, and the general approach to keep things simple, and allow testing.

What is Object Oriented Javascript

Javascript doesn't allow object orientation in a class-based style. Rather Javascript accomplishes object orientation using what is known as prototype-based programming. For a better description of prototype-based programming, we will use Mozillas definition:

Prototype-based programming is a style of object-oriented programming in which classes are not present, and behavior reuse (known as inheritance in class-based languages) is accomplished through a process of decorating existing objects which serve as prototypes. This model is also known as class-less, prototype-oriented, or instance-based programming.

Simply put, we will be building an object in Javascript, then adding Prototype functionalities to this object. This will allow other objects to "inherit" these functionalities. As with class-based object oriented programming languages, new objects of this variables can be made using the new keyword. To get a better grasp, we'll have some demos in a section further ahead. Until then, just understand that Javascript is attempting to mimic tradtional object orientation, but does so by using a prototype-based system. This syntax will also be greatly cleaned up in ECMA 6, which we will discuss further later on in this post.

Why would I want to Use Object Orientation

For those developers who may not understand why we want to use object orientation, object orientation allows us to make our code more modular. These days, web apps code and complexity has increased significantly. What was once passed off to a server for compilation, or simply not possible, has now been placed on the front-end of web applications. This means there is more code then ever before running on a users browser while viewing a web app. Furthermore, with the introduction frameworks like Node-Webkit, Cordova, or even html5 games, we have whole applications that take place on the client-side, with little to no connection to a back-end environment.

As our code complexity and density increases, we have to be smarter about the ways we architect our apps. Gone are the days we simply store this data in a couple files, place it in the window namespace, and call what we need. Today we have to be careful about overriding other namespaces, we have larger teams who need to be able to work on our code, and we need a familiar architecture and standards that help integrate new team members. Now I'm not saying object orientation will answer all these problems, but it certainly is a step in the right direction. In fact, lets look at why my workplace moved to this style of object oriented JavaScript.

We had been developing a small "game", allowing simple actions like moving and actioning items. Before this decision, our app had been a standard angular app. Once we decided to add some gameplay, we quickly prototyped our game with CreateJS and moved forward using Canvas. We had used the OO like programming with Angular, but had rarely dwelved deep into construction full OO systems with Javascript. After our first sprint, our code was a mess. We had gigantic main.js file full of code smells, duplication, and deep dependencies. It was so bs, that only one developer knew what was truly happening in that file. When new team members were added to the project, they would avoid working on that area of the app.

It was a bit to late, but we decided we needed to better architect our app, and moved to a stronger OO system. Of course, myself and the other developers come from a heavy Java and C# background, so the move was the simplest one to decide upon. We searched up what some of the best approaches to object orientation in Javascript were, and I gave the book "The Principles of Object-Oriented Javascript" by Nicholas Zakas a read. I won't go into detail about each progresive step we took, but after working on a number of apps, we came across a style of OO Javascript that we all agreed on.

Don't worry if you don't understand Object Orientation yet, we'll explain it step-by-step in the next section!

How Do We Use Object Orientation

Lets start at the basics. In object orientation, our first step is to split logical pieces of the code into objects. If you don't understand, pretend you were programming me as a person into your code. Well we could create an object called Denny that has all my properties, as such.

var Denny = {

class: "Mammal",

name: "Denny",

eyeColor: "blue",

height: "5ft10",

weight: "Too Much",

faviouriteBand: "The Beatles",

programsIn: ["Javascript", "C#", "Java"],

sayHello: function () {

console.log("hello");

},

payTaxes: function () {

friendDoesTax();

console.log("You are now broke");

},

eat: function () {

console.log("you eat something");

},

};

Great, we have some properties and functions of an Object. But what if we wanted to make another person? Well they would require us to create a whole new object manually. We'd have to make sure we place the same properties in, and that they output correct. Alright, so lets do that.

var Jim = {

class: "Mammal",

name: "Jim",

eyeColor: "green",

height: "6ft1",

weight: "Probably better shape then Denny",

faviouriteBand: "The Band",

programsIn: [],

sayHello: function () {

console.log("hello");

},

payTaxes: function () {

payToOverseasBank();

console.log("Still has more then Denny");

},

eat: function () {

console.log("you eat something");

},

};

Great, but now we run into a number of issues. Lets say that we suddenly have a standard way we need to pay taxes. Now we must go into both objects and change their function for payTaxes.

var newTaxFunction = function () {

payToTheMan();

};

Jim.payTaxes = newTaxFunction;

Denny.payTaxes = newTaxFunction;

Furthermore, there is a lot of shared code between these types. We want a way to encapsulate this data, but also also us to share code. So lets break this down logically.

Lets return to our example of coding me into your project. At the root, what am I? Now, we should always attempt not to over-architect our application. At this point, lets assume that at my root, I am a Mammal. So we'll create a Mammal class.

var Mammal = function (name) {

this.name = name;

eat("Milk");

};

Mammal.prototype = {

constructor: function (name) {

this.name = name;

this.eat("meat");

},

eat: function (food) {

console.log("You ate lots of " + food);

},

};

Great, now for an explanation of what we wrote. The top mammal function is our object itself. It will be what someone calls when using your code. Inside, by habit, we place the default instance values and the constructor. Our team has come to an agreement keeping the methods in the prototype, while placing instance variables and initalization into the object declaration. In our example, we can identifiy two types of variable/function exposure. public and privileged. The functions in the prototype are public functions. That is, they can be called, but they do not have access to the Mammals private functions or variables. We do not have any currently, so this isn't a problem. We will look at private variables shortly.

We also can see an example of a privileged variable, which is name. It is attached to the object itself (using this.name), so we can call the variable from outside on the Mammal function. If you come from a Java or C# background, don't mistake these naming conventions with their conventions. Privileged functions are similar to public functions in these languages, in that they can call their own objects private methods, and be called externally. Public function/variables in javascript are a little different, again, they can only call privallaged methods.

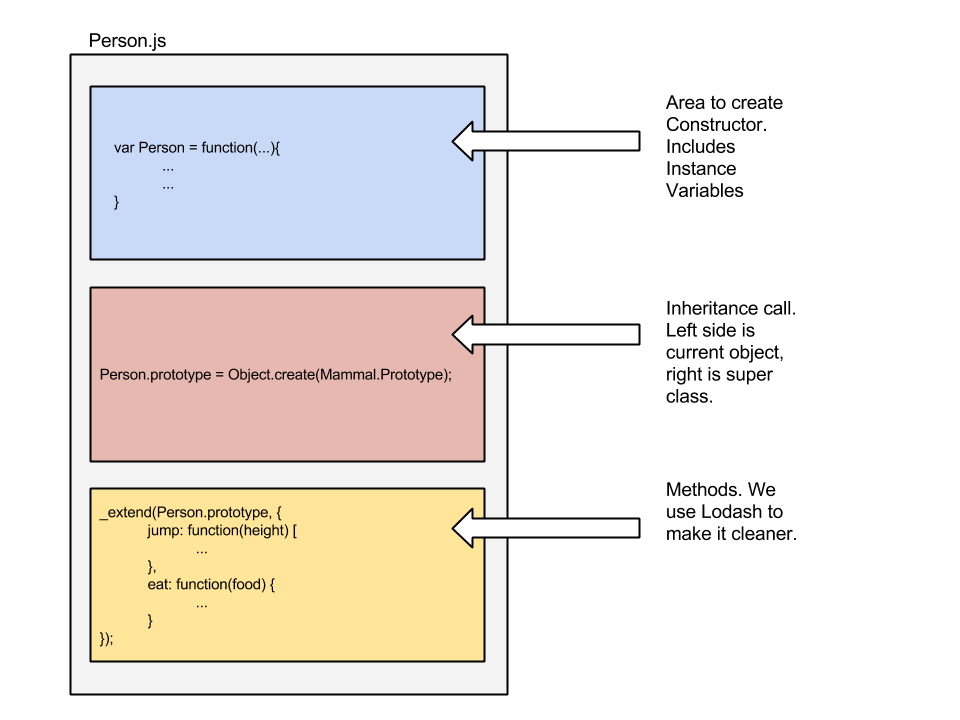

So lets see how inheritance works with this new object. Now that we have Mammal, lets build a Person class, and extend it from Mammal. I've created a small visual guide on how we normally construct these objects.

The code would look as follows:

/**

* Object Declaration. Includes Constructor and Instance Variables

**/

var Person = function (name, age, height, weight) {

Mammal.call(this, name);

this._age = age;

this.height = height;

this.weight = weight;

Object.defineProperty(this, "age", {

get: function () {

console.log("i'm super secret");

return this._age;

},

set: function (a) {

console.log("setting");

_age = a;

},

});

};

/**

* Inheritance using Prototypes, this uses Lodash to simplify the process.

**/

Person.prototype = Object.create(Mammal.prototype);

/**

* Public Methods

**/

_.extend(Person.prototype, {

jump: function (height) {

console.log(

this.name +

", who is " +

this.height +

" ft tall, jumped " +

height +

" feet."

);

},

eat: function (food) {

console.log("you've moved on from" + food);

},

});

So as before, we initalize our object and set up the instance variables in the Person function. Now, we tell this new Person functions prototype to be based from Mammal.prototype. For an extended read on this process, I recommend the post at dailyjs. The final section, our public methods, are similar to our previous Mammal methods, except these ones must also use the original Mammal methods. We could simply add our methods individually to Person.prototype, but I prefer this syntax. It's clean, and is a great opportunity to use the Lodash library!

But what about those other methods we haven't created from our inital demo. Well these variables and functions aren't necessarly something all people have. So we have a number of options. We could further extend the Person class. Perhaps only adults can pay taxes? This thought process is exactly how you should start thinking when using object orientation. There are many more questions on what to do with OO, and how far inheritance should go, so if your unfamiliar with the topic, I highly recommend researching it some more!

Another option in Javascript is to add a single method to that object. This isn't the most recommended solution, but what if we were creating all these different people, and we decided we wanted one object to have one more function. We can simply add a function to that object, and it will only exist for that single object.

Further more, if any of the objects change the prototypes function such as, that change will replicate across all objects of that type.

The style we use is one that we as a team decided upon. Our early iterations of object oriented Javascript worked just fine, but were often confusing to new team members. They didn't have a patterend look, were messy, using public functions, private functions, and privileged functions. Some team members were upset when they could not test private functions. Of course, this is a matter of debate itself, but we felt moving to this new system would allow team members to choose if they wanted to test private functions.

So there are no Private Functions

When our team first started using object orientation, we made heavy use of private functions. Why wouldn't you? It's a great way to hide functions that are only intended to be used within the function itself. It helps users when their using your library, by hiding the other calls. Their were two major reasons we moved away from the use of private variables/functions.

- Performance. In most class-based object-oriented languages, you cannot change the method externally from the object. Therefore, you know that all objects functions are the same. The intended way to change these methods is by using inheritance and overriding these methods. Since these cannot change, these languages will often store that particular method in memory to be called by all instantions of that class.

On the other hand, in javascript we can change that function at any time. Therefore, each function that an object holds is it's own spot in memory. This decreases the performance of these functions between 10 and 90%. My work often focuses around HTML5 apps, and any bit of performance in this field is a big deal.

If you've been following along, you may have noticed that I earlier had mentioned that changing a prototype's function on one object will propogate it to the rest. Thats great news, it means that all objects functions using a prototype will point back to a single prototype, greatly increasing performance.

- Style. When we previous had relied on private and privileged functions, we ended up with a lot of binding and variable declarations. This look ended up confusing a lot of new team members on where each part of code would be. By splitting into these declared sections, we can speed up the adoption rate for new team members.

Thats great, but we still want to indicate to user's which functions they should not be using. To do this, we place an underscore ahead of those variables and functions. This does not stop the user from using those variables and functions, but is the general standard to indicate a private value.

Polymorphism in Javascript

By extending the prototype of our Object, we can also use polymorphism where necessary. Of course, since javascript is not strongly typed, there is no hard requirements on variables being passed. If we want to assure that variable is of a certain type, we can always do a type check on the passed variable, for example.

function liveBirth(mammalObject) {

if (mammalObject instanceof Mammal) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

ECMA 6 (2015)

There will be some nice syntactical sugar for object orientation in Javascript in the next Javascript release. For example, our Person example would look like this in ECMA 6 (2015):

class Person extends Mammal {

constructor(name, age, height, weight){

super(name);

this.height = height;

this.weight = weight;

}

jump(height){

console.log(...);

}

eat(food) {

console.log(...);

}

}

We left out the define property, which will still be the same, but you can see how much tidier this will be. Under the hood, the same things will be happening, but will just have a cleaner look. This new ECMA6 style does not allow private functions for the same reason that we avoid private functions currently.

I hope this guide has helped you out while learning object oriented Javascript. As with everything in Javascript, you have many ways to do each action, so if something in here is not to you liking, do whatever works for you. The most important thing is to get your app running. Thanks!