Introduction to Tree Shaking

Introduction

It's been some time since I started the reducing Javascript bundle size series, but today we are going to take a look at one of the most misunderstood tactics for reducing the size, tree shaking. Tree shaking has a lot of buzz to it, so it's worth investigating.

We are going to examine what tree shaking means, how it works, how it helps both dead code elimination and module dependencies, and finally what we should expect from it. Let's dive in first with a recap on dead code elimination.

Brief Overview of Dead Code Elimination

We took a deeper dive into what dead code elimination is in a previous post in this series. None the less let's have a quick refresher on what dead code elimination is, as it will be pivotal to understanding Tree shaking, as tree shaking uses the same technique. If you would like a deeper dive into the topic, I do recommend looking at the linked article above.

Dead code elimination (DCE) is the process of removing code that is either unused or inaccessible. Tools like Terser usually handle DCE in conjunction with build systems like Webpack. An example of DCE would be the following example

function selectClothes(type) {

if (type === "shirt") {

return {

type: "shirt",

amount: "$10",

};

} else {

return {

type: "pants",

amount: "$12",

};

}

return {

type: "hat",

amount: "$5",

};

}

function selectAccessory() {

return {

type: "ring",

amount: "$40",

};

}

const data = selectClothes("shirt");

console.log(data);

In the above example, it is impossible ever to reach the return of type: hat. That's because there is an else beforehand, making the code inaccessible. Terser will try to determine this and remove these unused examples. Similarly, the selectAccessory function was never executed in this code, and therefore can be removed as well. But, if we run Terser over the file, you'll notice it isn't removed

npx terser index.js -c

function selectClothes(type) {

return "shirt" === type

? { type: "shirt", amount: "$10" }

: { type: "pants", amount: "$12" };

}

function selectAccessory() {

return { type: "ring", amount: "$40" };

}

const data = selectClothes("shirt");

console.log(data);

Why wasn't this removed? Because Terser isn't positive the function isn't used somewhere else, and won't make that call. It only removes code that it can guarantee won't be used. If there's any ambiguity, it will take no action. What we need is to isolate this file as a module. Encapsulating a file can be done with several different module styles, but CommonJS (CJS) and ECMAScript Modules (ESM) are undoubtedly the most popular, with ESM the standard for Front-end, and CJS still commonly used in NodeJS.

Regardless, at this point, you don't even need to know what "style" this is in. By running a build with Webpack, we can see the difference.

For all of the webpack examples, I am going to keep the code mangled. That's because I want to give an idea of how this code will look. I've used console.log(name) to provide us with spots to hunt.

npx webpack

!(function (e) {

var t = {};

function n(r) {

if (t[r]) return t[r].exports;

var o = (t[r] = { i: r, l: !1, exports: {} });

return e[r].call(o.exports, o, o.exports, n), (o.l = !0), o.exports;

}

(n.m = e),

(n.c = t),

(n.d = function (e, t, r) {

n.o(e, t) || Object.defineProperty(e, t, { enumerable: !0, get: r });

}),

(n.r = function (e) {

"undefined" != typeof Symbol &&

Symbol.toStringTag &&

Object.defineProperty(e, Symbol.toStringTag, { value: "Module" }),

Object.defineProperty(e, "__esModule", { value: !0 });

}),

(n.t = function (e, t) {

if ((1 & t && (e = n(e)), 8 & t)) return e;

if (4 & t && "object" == typeof e && e && e.__esModule) return e;

var r = Object.create(null);

if (

(n.r(r),

Object.defineProperty(r, "default", { enumerable: !0, value: e }),

2 & t && "string" != typeof e)

)

for (var o in e)

n.d(

r,

o,

function (t) {

return e[t];

}.bind(null, o)

);

return r;

}),

(n.n = function (e) {

var t =

e && e.__esModule

? function () {

return e.default;

}

: function () {

return e;

};

return n.d(t, "a", t), t;

}),

(n.o = function (e, t) {

return Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(e, t);

}),

(n.p = ""),

n((n.s = 0));

})([

function (e, t) {

const n =

"shirt" === "shirt"

? { type: "shirt", amount: "$10" }

: { type: "pants", amount: "$12" };

console.log(n);

},

]);

Webpack has made a lot of optimizations, so the code can be quite a bit trickier to read, but notice that there is no instance of type:ring existing anymore? It recognized that the function was never called internally for the module, and was therefore dead, and eliminated.

Note: Moving forward, we will be calling these modules, following the ESM style. Assuming these are encapsulated pieces will make them much more comfortable to think about. We'll discuss why we are using ESM soon.

So what is tree shaking

To start with the idea of tree shaking, the easiest way I found to think about it was to picture it as dead code elimination across modules. So far, our dead code elimination only works internally to a given module. It will check if code is inaccessible, or ever called, and remove it from that module. But what if we had a module that is never called? Or only a small piece of it is? Can we remove it, or the portions unused within the unused module, from our codebase then?

The answer is yes, and some of it might be already happening for you, and you didn't know. Let's take a look into how this is possible, and how this could be useful to you. The steps we'll follow to get there are:

- Understand why it's called tree shaking, so we understand fundamentally what our goal is.

- How to code in such a way that allows optimal tree shaking

- Seeing a code example of this style

- Investigating what scenarios are most beneficial for the application of tree shaking

Why is it called Tree shaking?

Let's stop a think a minute on how module dependency works. You tell Webpack the first file it should look in, usually something like src/index.js. From there, Webpack will open that file and might notice you are importing a.js. It will then note that the index has a dependency on a.js. After index, Webpack will look at a.js and scan it for dependencies.

Note: depending on the module system, there is some asynchronous loading to this, but let's talk about it synchronously for simplicity.

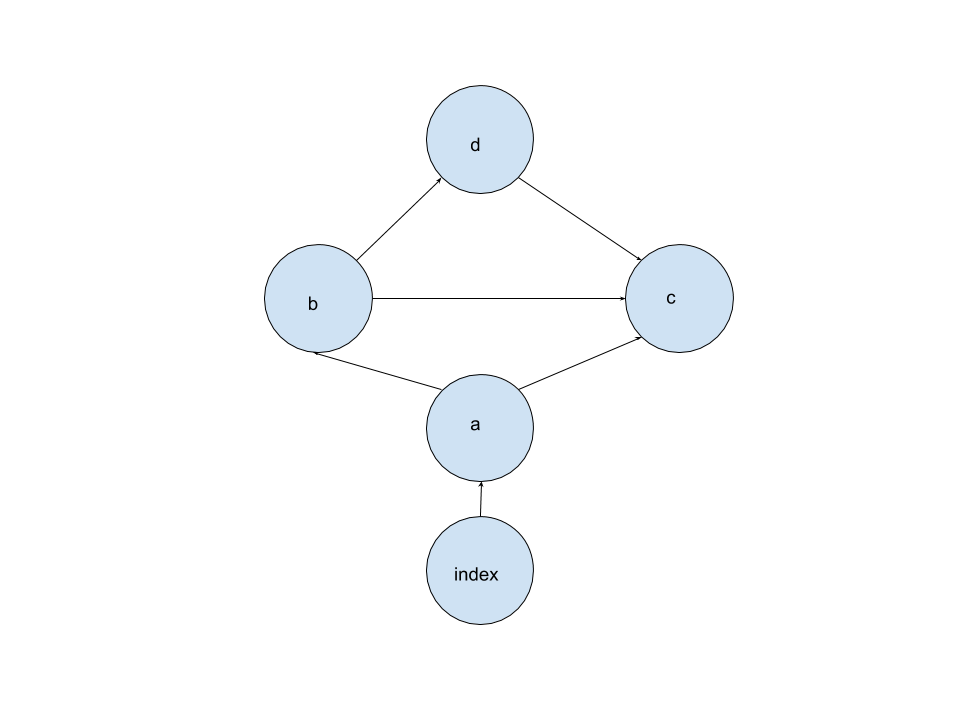

To get a better understanding of this, let's add some more files to our little project, with a couple of imports. Since we already have index.js, let's make four more files, named, a.js, b.js, c.js, and d.js. Then follow the steps for each file below

a.js

import b from "./b";

import c from "./c";

export default function checkIn() {

b();

c();

console.log("This is a!");

}

b.js

import c from "./c";

import d from "./d";

export default function checkIn() {

c();

d();

console.log("This is b!");

}

c.js

export default function checkIn() {

console.log("This is c!");

}

d.js

import c from "./c";

export default function checkIn() {

c();

console.log("This is d!");

}

index.js

import a from './a';

function selectClothes(type) {

...

}

const data = selectClothes('shirt');

console.log(data);

console.log(a);

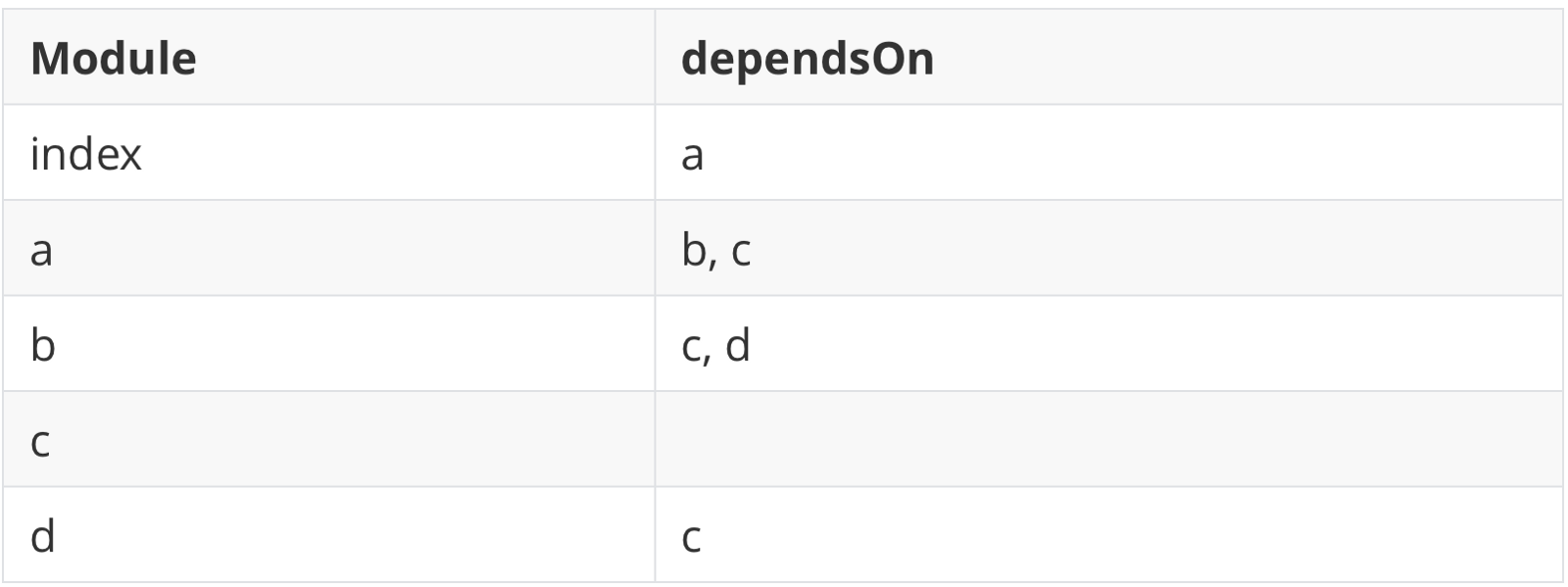

Great, so looking at the code above, we can map out the dependencies. Each module can depend on 0...n modules. Let's place these dependencies in a table.

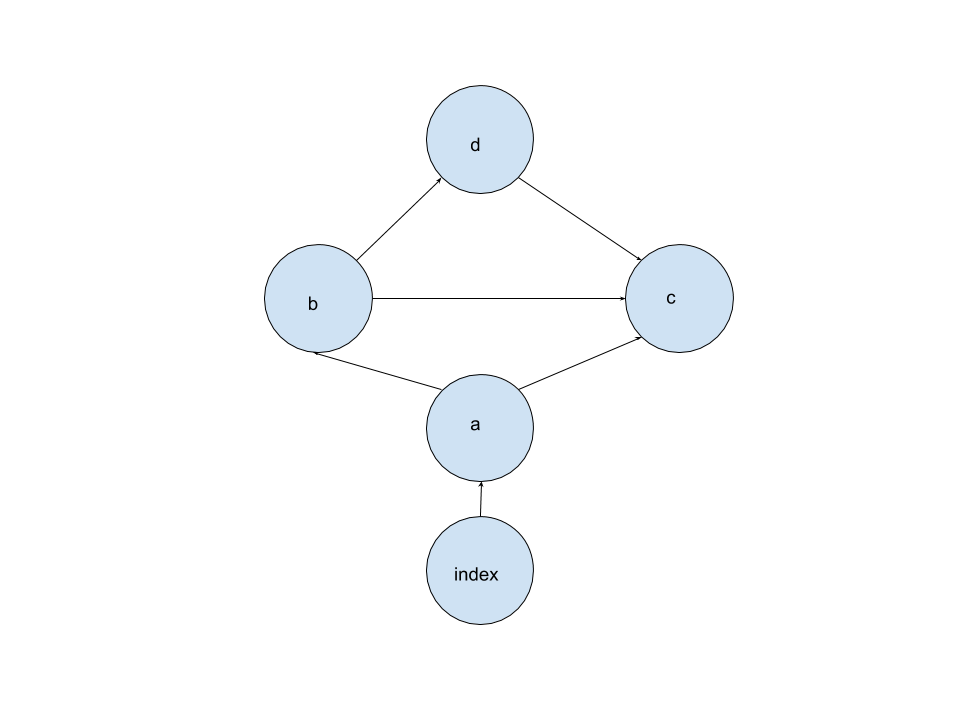

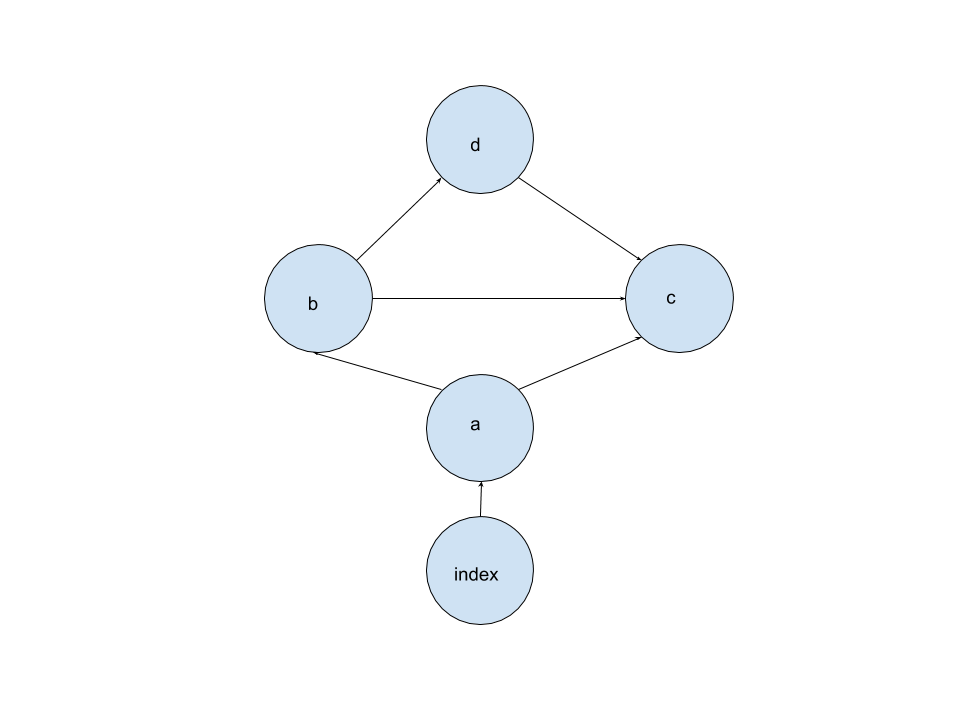

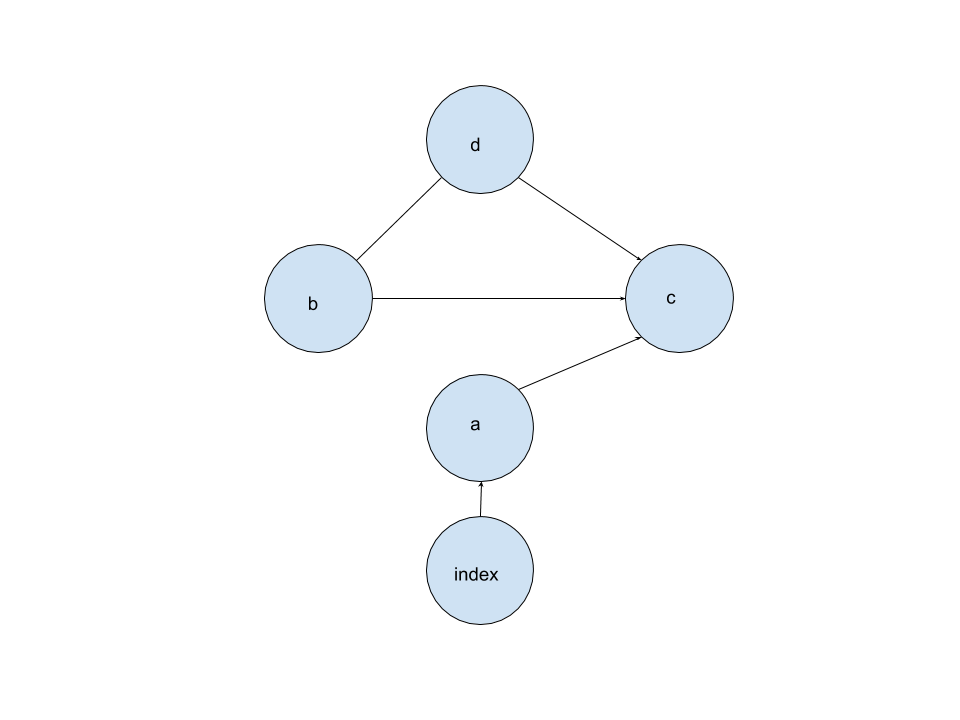

With our simple dependency table done, lets plot this out as a graph. A circle will represent each module, and a line indicates a dependency. The arrow indicates it's the dependee module. For our example, the graph should look something like this

Looks a bit like a tree, doesn't it? Our set of modules is still rather small, and the dependencies are somewhat interlocked. It would be handy to see some more significant projects, to get a better visual representation before we move forward. There's a great tool to do this, the Webpack Analyzer. It will build these dependency graphs for us. First, in the root of our project run:

npx webpack --profile --json > webpack-stats.json

The above command will create a webpack-state.json file. Now, we can upload this on the analyzer website here. But if you navigate to the modules tab, you'll notice it looks a little underwhelming:

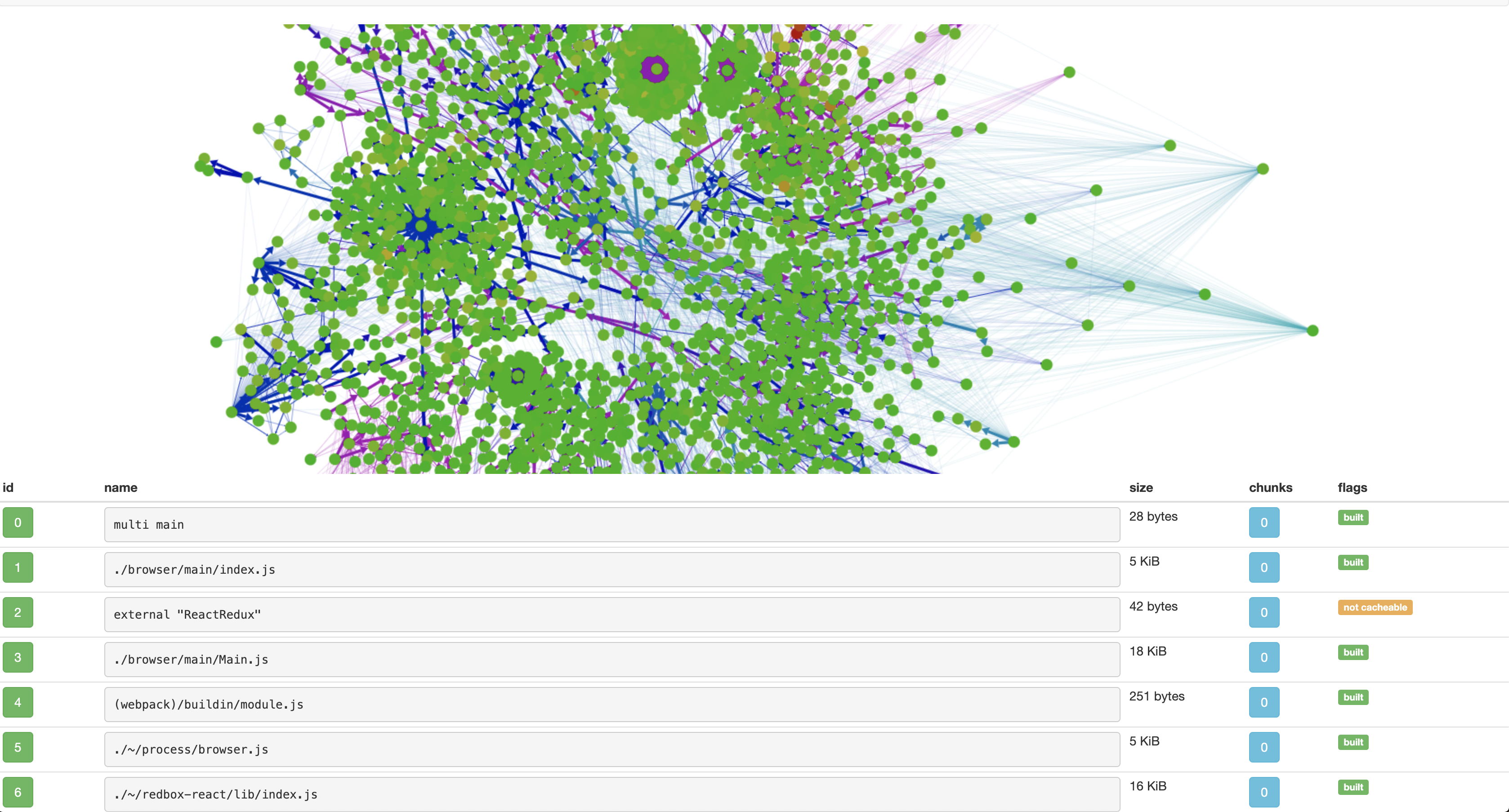

Well, our webpack bundles these together as a single chunk. Therefore, we only see it as a single dot. But we know the process now, how about we try it on a more significant project! I'm going to try it on Boostnote, a cross-platform markdown editor written in React.

First we'll clone Boostnote with:

git clone git@github.com:BoostIO/Boostnote.git

cd Boostnote

npx webpack --profile --json > webpack-stats.json

If we upload the webpack-stats to the Webpack Analyzer, we get something like this:

Now that's a tree! Unfortunately, the main.js is actually in the middle of all of these, and creating it as a web outwards is the best use of space, but if we were to imagine it was the base, everything would expand outward in a more classical "tree" form, with sets of nodes, and leaf nodes.

So what does this have to do with tree shaking? Well now that we know our module structure is inherently made up of a tree of nodes, what happens if we were not to use some dependencies. Given our project above again

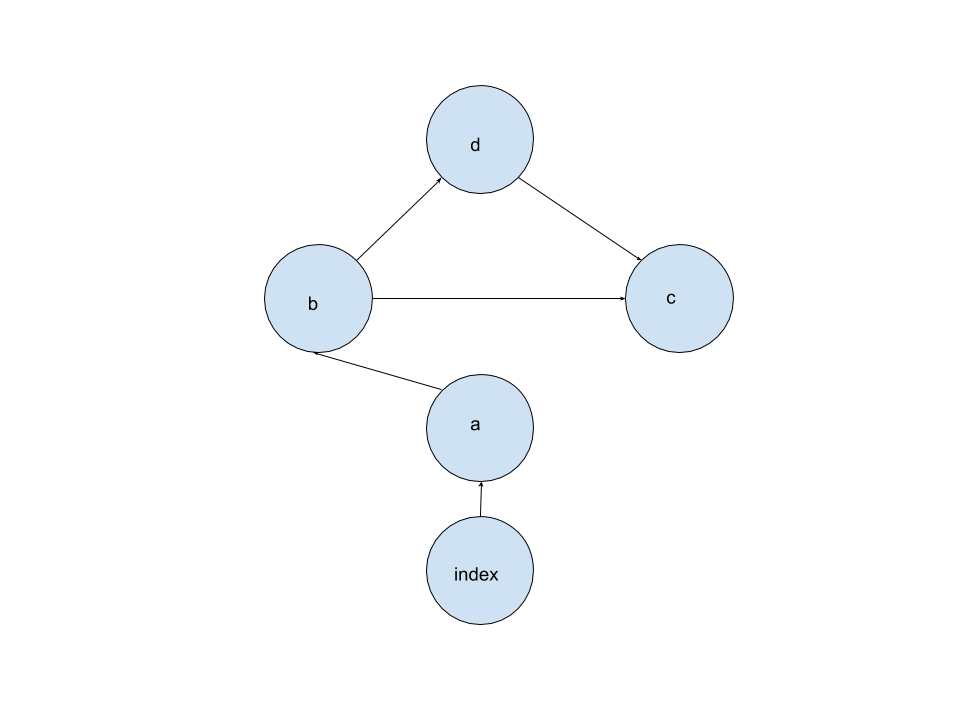

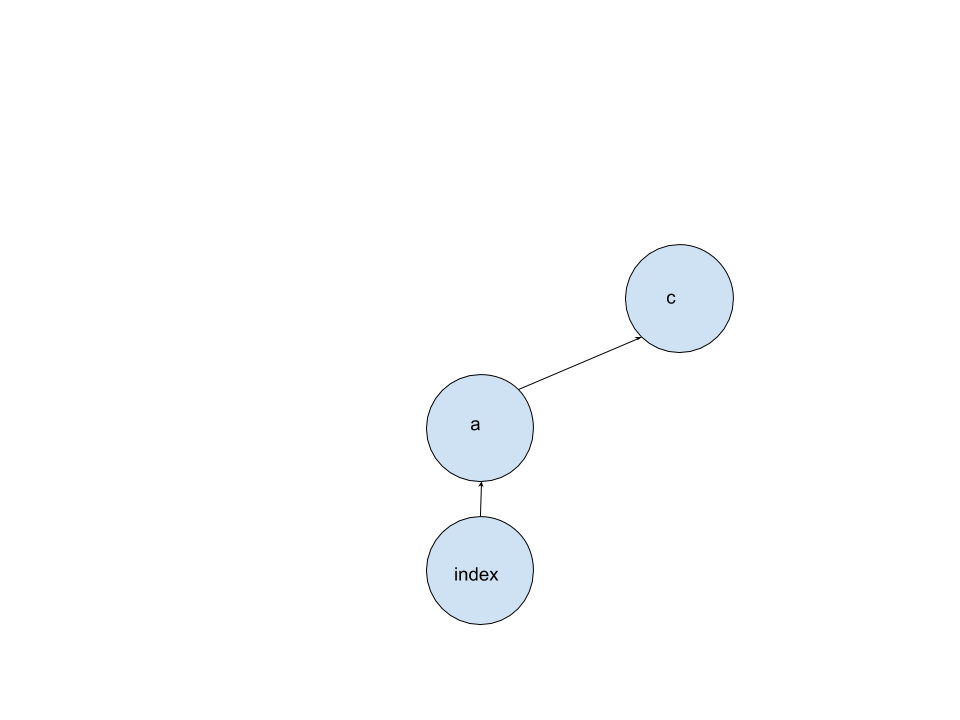

What would happen if we removed the dependency on a -> c? Our dependency graph would now look like this:

Although the dependency between a -> c is now gone, all the modules are still required in some fashion. When Webpack runs through all the modules, it will recognize that each one is imported at some point, and add them to our bundled chunk.

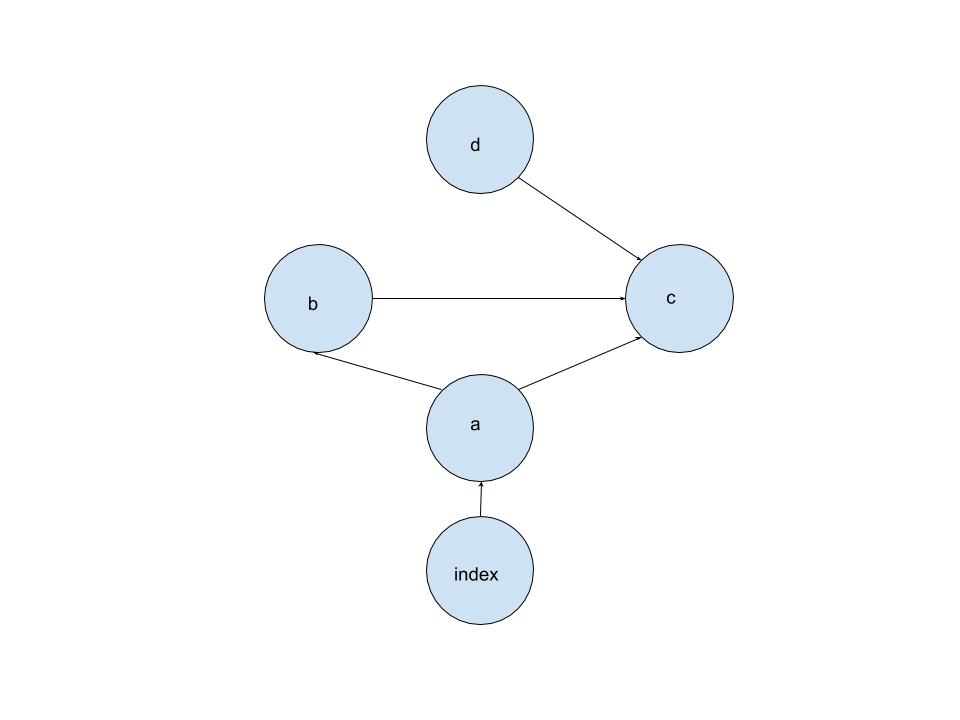

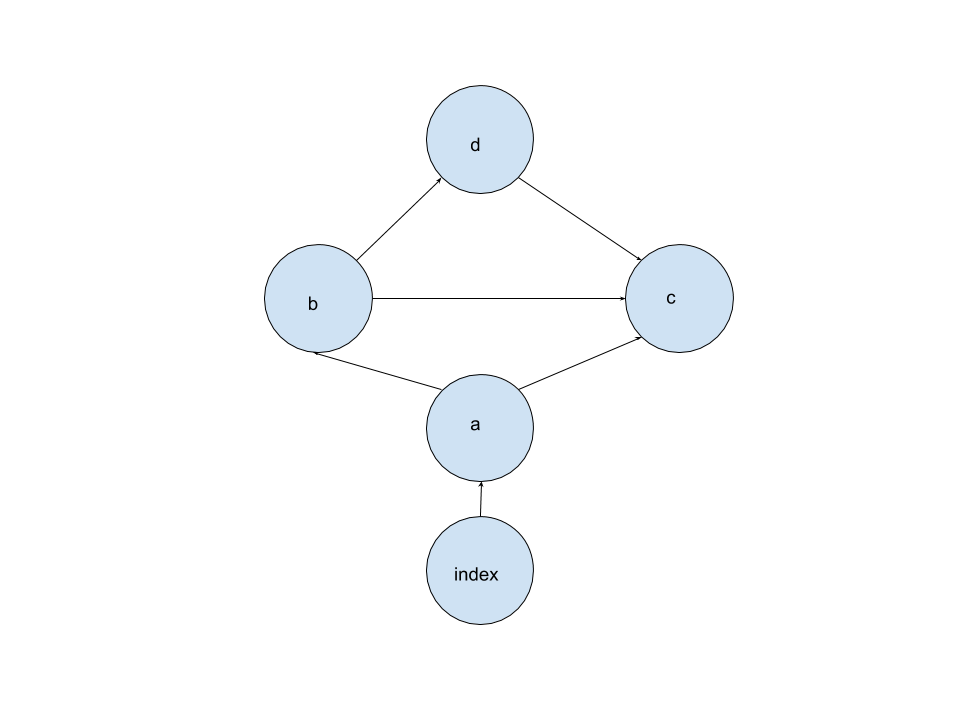

Let's return our a -> c dependency, but now remove our b -> d dependency. What would look different now?

This is where tree shaking starts to come into play. When we are building these trees, and our bundles from them, there is a significant relationship we have to recognize. We begin at the index (or whatever we tell Webpack is our starting module). Each step through the graph is a dependsOn relationship. In the example above, although d does depend on c, there is no module depending on d. Therefore, tree shaking will occur, and our actual tree will be:

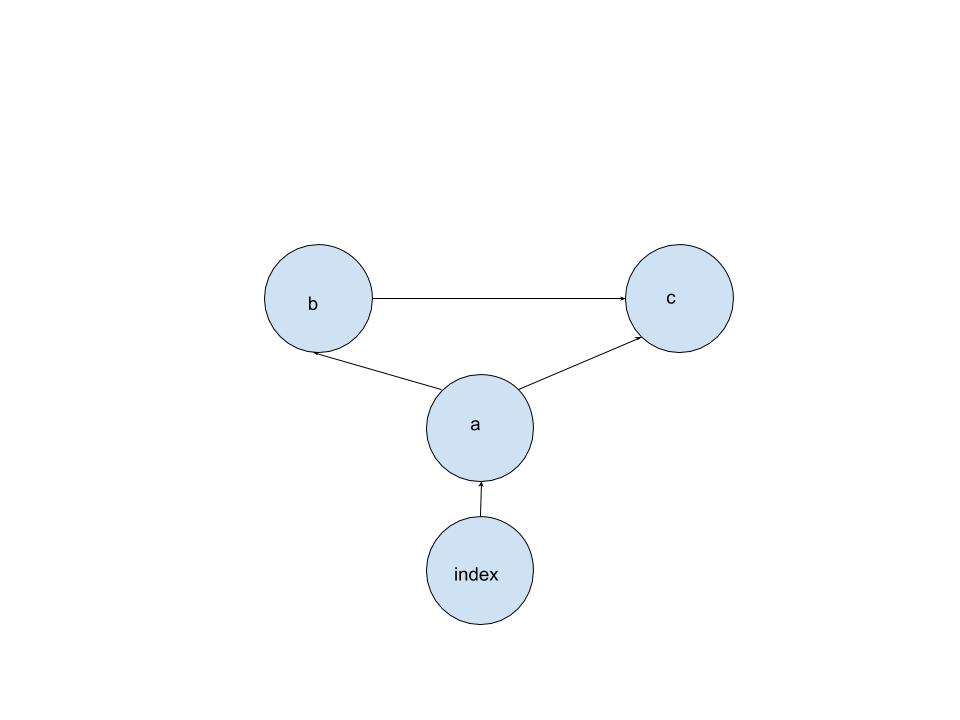

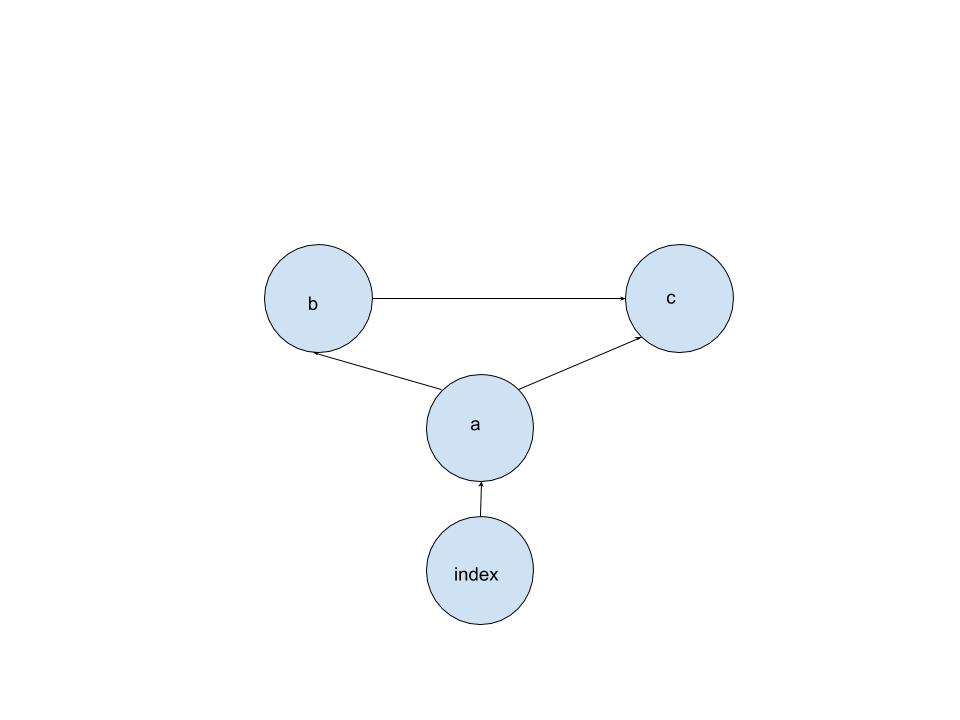

Tree shaking has occurred, and we've removed an unneeded module from our dependencies! Now, this was a simple example, what about multiple dependencies? Let readd our b -> d dependency, and remove our a -> b dependency instead.

Just like last time, lets scan over the modules, and see where their dependencies are now. Each module has a dependsOn relationship except for b. Therefore, tree shaking will take place, and we get the following tree:

What happened to our d module? Well, since no module depended on b, it was removed. Once b was removed, there was no path from our base (index) to the d module anymore. So as you can see, when we "shake" the tree, we are removing unused modules from our codebase.

Now here's a critical disclaimer: The above examples aren't quite "tree shaking." It is, in a technical sense, tree shaking, but not what we usually refer to as tree shaking. Instead, I've been showing you module dependencies, and how your module bundler will build a dependency graph (and ultimate bundle) from those modules. But we're close, and the above process is fundamental to tree shaking. We've just skipped a step in the tree shaking process to make it easier to follow at a high level.

Before we talk about the last step, we need to jump into what static analysis is, and how ESM plays a role within it.

CJS vs ESM

There's a pretty long and detailed history for modules systems within the javascript ecosystem. UMD, AMD, CJS, ESM, and more. Some of these systems, like AMD, were prominent on the front-end, with implementations like RequireJS being pretty popular.

Meanwhile, as Node gained popularity, so to did its module system, CommonJS. CommonJS was specced originally for use strictly on NodeJS. But just as NPM had initially been a NodeJS package management system before it devoured Bower, so too did CJS make it's way to the front end.

Before long, CJS was often the 'defacto' way to build front-end applications and libraries. Module bundlers like webpack often assumed that CJS was going to be the used spec. But CJS is not statically analyzable, because it does not have a static structure. What does that mean?

Let's take a look at an example of some CJS code:

var y;

if (x === 1) {

y = require("somelib");

} else {

y = require("someotherlib");

}

We cannot determine what y will be, and what it imports, until runtime. It has a dynamic structure. What about when we export code?

exports.add = (x, y) => x + y;

exports.wreckItAll = () => (exports.add = (x, y) => x * y);

Again, the code is dynamically structured; therefore, we can change our exports at runtime. We can't be positive about what is being imported or exported, and what of that is used. These values can all change at runtime.

Then we get to Ecmascript Modules. ESM is the newest spec which has been in the works for some time and is the official ECMAScript proposal. ESM is statically structured meaning that all imports and exports must be defined at compile time (rather than runtime).

Because of this, we can guarantee what modules are being imported and exported. Static structures have several positive benefits, which we can dive into in another blog post (like resolving circular dependencies), but it also means that we can analyze the code and determine which exports are used at compile time.

Note: ESM has a ton of benefits not brought up here, such as asynchronous loading, faster lookups, etc. We'll dive into these in a future post.

What does that look like in code?

Let's jump back to our previous examples with a.js, b.js, c.js, and d.js. As I said back there, we weren't quite doing tree shaking yet; we were following a module dependency chain. But let's take our example one step further. Assume we are back at our original dependency, like so:

And let's take a look at b.js code.

import c from "./c";

import d from "./d";

export default function checkIn() {

d();

c();

console.log("This is b!");

}

Everything is as it should be, and our dependency graph accurately represents the modules. But, what happens if it turns out we don't use d? But we don't remove the import? Like so:

import c from "./c";

import d from "./d";

export default function checkIn() {

c();

console.log("This is b!");

}

If this were CJS, we would still have the same graph as above, because we cannot guarantee that at runtime, this gets called somehow. But we can determine it is not called at compile time with ESM, and therefore can adequately tree shake it.

Here is our example after bundling in webpack, notice there is no console.log("This is d!").

!(function (e) {

var t = {};

function n(o) {

if (t[o]) return t[o].exports;

var r = (t[o] = { i: o, l: !1, exports: {} });

return e[o].call(r.exports, r, r.exports, n), (r.l = !0), r.exports;

}

(n.m = e),

(n.c = t),

(n.d = function (e, t, o) {

n.o(e, t) || Object.defineProperty(e, t, { enumerable: !0, get: o });

}),

(n.r = function (e) {

"undefined" != typeof Symbol &&

Symbol.toStringTag &&

Object.defineProperty(e, Symbol.toStringTag, { value: "Module" }),

Object.defineProperty(e, "__esModule", { value: !0 });

}),

(n.t = function (e, t) {

if ((1 & t && (e = n(e)), 8 & t)) return e;

if (4 & t && "object" == typeof e && e && e.__esModule) return e;

var o = Object.create(null);

if (

(n.r(o),

Object.defineProperty(o, "default", { enumerable: !0, value: e }),

2 & t && "string" != typeof e)

)

for (var r in e)

n.d(

o,

r,

function (t) {

return e[t];

}.bind(null, r)

);

return o;

}),

(n.n = function (e) {

var t =

e && e.__esModule

? function () {

return e.default;

}

: function () {

return e;

};

return n.d(t, "a", t), t;

}),

(n.o = function (e, t) {

return Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(e, t);

}),

(n.p = ""),

n((n.s = 0));

})([

function (e, t, n) {

"use strict";

function o() {

console.log("This is c!");

}

n.r(t);

const r =

"shirt" === "shirt"

? { type: "shirt", amount: "$10" }

: { type: "pants", amount: "$12" };

console.log(r),

console.log(function () {

o(), console.log("This is b!"), o(), console.log("This is a!");

});

},

]);

Finally, let's look at one last example of tree shaking, tree shaking a module that has multiple exports. Since tree shaking is also a piece of dead code elimination, and we can statically analyze our code, not only can we aid in the process of module dependencies, but it also aids in discovering which code can be eliminated. We're going to go back to our original structure, but with some slight alterations:

b.js

import c from "./c";

import { add } from "./d";

export default function checkIn() {

add(1, 1);

c();

console.log("This is b!");

}

And let's update our d.js API to match:

d.js

import c from "./c";

export function add(x, y) {

c();

return x + y;

}

export function multiply(x, y) {

c();

return x * y;

}

Now, our dead code elimination cannot delete exported functions, because they could be used outside of this module. When one was using CJS, our code was not statically structured; therefore, we couldn't ever be sure if the code was used, and especially not before compile time.

But, with ESM, Webpack (or most module bundlers) can examine this code, and determine if these functions are ever imported or used. If they are not used, like multiply above, tree shaking takes place, and the export syntax is removed. Dead code elimination takes over as usual and notices the function is not used and is removed from the codebase. Let's see that in action, again running

npx webpack

!(function (e) {

var t = {};

function n(o) {

if (t[o]) return t[o].exports;

var r = (t[o] = { i: o, l: !1, exports: {} });

return e[o].call(r.exports, r, r.exports, n), (r.l = !0), r.exports;

}

(n.m = e),

(n.c = t),

(n.d = function (e, t, o) {

n.o(e, t) || Object.defineProperty(e, t, { enumerable: !0, get: o });

}),

(n.r = function (e) {

"undefined" != typeof Symbol &&

Symbol.toStringTag &&

Object.defineProperty(e, Symbol.toStringTag, { value: "Module" }),

Object.defineProperty(e, "__esModule", { value: !0 });

}),

(n.t = function (e, t) {

if ((1 & t && (e = n(e)), 8 & t)) return e;

if (4 & t && "object" == typeof e && e && e.__esModule) return e;

var o = Object.create(null);

if (

(n.r(o),

Object.defineProperty(o, "default", { enumerable: !0, value: e }),

2 & t && "string" != typeof e)

)

for (var r in e)

n.d(

o,

r,

function (t) {

return e[t];

}.bind(null, r)

);

return o;

}),

(n.n = function (e) {

var t =

e && e.__esModule

? function () {

return e.default;

}

: function () {

return e;

};

return n.d(t, "a", t), t;

}),

(n.o = function (e, t) {

return Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(e, t);

}),

(n.p = ""),

n((n.s = 0));

})([

function (e, t, n) {

"use strict";

function o() {

console.log("This is c!");

}

function r() {

o(), console.log("add"), o(), console.log("This is b!");

}

n.r(t);

const u =

"shirt" === "shirt"

? { type: "shirt", amount: "$10" }

: { type: "pants", amount: "$12" };

console.log(u),

console.log(function () {

r(), o(), console.log("This is a!");

});

},

]);

Notice above, console.log('multiply') never exists. Tree shaking removed that code for us. What does the dependency graph look like? Well, like our original graph, just with dead code removed from the d module:

Caution for Tree shaking as an optimization

Now that you understand what exactly tree shaking is, and how it can be helpful for us, I want to start by saying, it's usage for you will vary wildly. Depending on what exactly you're building, there's going to be a difference to how you set up your bundles, and how effective setting up tree shaking will be.

That's because tree shaking is handy for removing modules and code that is unused. Depending on what you are building that could be incredibly handy or provide almost no value to you. Tree shaking has become somewhat of a buzzword in the web development community as an almost magical way to reduce bundle size. And in some areas, it can be incredible. But I want to set the expectation early, that it's likely not going to be the case for you.

For a small cautionary tale, my colleagues and I decided we wanted to reduce the bundle size of our application. We had several plans, but tree shaking was undoubtedly one of our top priorities. The trouble was, our code was a mix of CJS and ESM. So we built several code mods to migrate our system over to ESM. Before the migration, we tested out what the possible bundle size reduction could be, by forcing babel to build into ESM. It appeared we could reduce the bundle by anywhere close to 20%. That was huge!

We completed the migration and reran the analyzer. We reduced our core-bundle by between 3 - 5%. Still useful, but nowhere near the level we had been hoping. So why were our numbers so far off? Well in our early tests, when we forced the CJS into ESM, importing works different between the two specs (namely default). When Webpack analyzed the code, it determined nothing was at the import location and would remove the module, despite us needing it, much inflating the tree shaking effect.

Building the code mods to migrate from CJS -> ESM took quite a bit of time and work. There are some unexpected edge cases between the two specs. I'm looking to open source the work we did, and will hopefully write a blog soon detailing the process!

Tree shaking web app vs library code

To understand how useful tree shaking will be for you, first determine how much-unused code is currently your codebase?

If you are building a web application, tree shaking will still come in handy, but the actual optimizations you get from it on your code will be minimal. It will vary if you have a lot of unused code in your codebase, but assuming that most of your codebase executes in some way, you likely won't see a significant reduction from this.

A more likely route you'll see a benefit is the libraries you use. Some libraries, especially UI libraries, will be tree shakeable by you. For an example of a project that is meant to be tree shakeable by you, react-dnd is not bundled in any way but built entirely in ESM. After importing the project into your web app, if your application is made with tree shaking, it will naturally tree shake react-dnd.

That also means, if you are developing a library, it's essential to set it up in such a way that users can tree shake elements they are not using! That's why you'll often see some of these libraries not bundle their library, but rather only pass it through Babel, and allow the user themselves to shake it.

Closing Thoughts

Despite my caution above, tree shaking, module dependency, and dead-code elimination are essential tools in your belt. They are fundamental for understanding ways to try and reduce the size of your Javascript bundle.

The next step we'll be taking is actually the core way I believe you can help reduce the Time-to-Interactive for your customers, and that is code splitting. We'll dive into that soon, and wrap up the reducing js bundle series.

If there's something you're interested in to see on this blog, or you think I should check out, be sure to contact me @gitinbit. All code here is available on Github. Cheers!

References and Further Reading

-

https://webpack.js.org/guides/tree-shaking/

-

https://medium.com/better-programming/reducing-js-bundle-size-58dc39c10f9c

-

https://medium.com/better-programming/reducing-js-bundle-size-a6533c183296

-

https://github.com/terser-js/terser

-

https://nodejs.org/docs/latest/api/modules.html

-

https://exploringjs.com/es6/ch_modules.html

-

https://nodejs.org/en/

-

https://webpack.js.org/

-

https://medium.com/@joeclever/three-simple-ways-to-inspect-a-webpack-bundle-7f6a8fe7195d

-

https://github.com/BoostIO/Boostnote

-

https://webpack.github.io/analyse/

-

https://reactjs.org/

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dependency_graph

-

https://github.com/umdjs/umd

-

https://requirejs.org/docs/whyamd.html

-

https://www.npmjs.com/

-

https://bower.io/

-

https://exploringjs.com/es6/ch_modules.html#static-module-structure

-

https://medium.com/@lawliet29/tree-shaking-in-real-world-what-could-go-wrong-b398c2b2ebbb

-

https://developers.google.com/web/fundamentals/performance/optimizing-javascript/tree-shaking/

-

https://babeljs.io/

-

https://developers.google.com/web/tools/lighthouse/audits/time-to-interactive